Ridiculous flooding

|

| |

The Sorrento West Business Park runs

between Roselle Street, I-5, Flintkote and Estuary Way. The older parts

were built out in the 1960s. Occupants are primarily a collection of hi-tech

companies in leased buildings. This district flooded September 1997, January

1997 and November 1996. The Sorrento West Business Park runs

between Roselle Street, I-5, Flintkote and Estuary Way. The older parts

were built out in the 1960s. Occupants are primarily a collection of hi-tech

companies in leased buildings. This district flooded September 1997, January

1997 and November 1996.

Remember the famous floods of September

of '97? Probably not there weren't any in the rest of the city. However,

less than 1 inch of rain caused Roselle Street to flood with two feet of

water, stranding motorists who had to be rescued from their trapped vehicles. Remember the famous floods of September

of '97? Probably not there weren't any in the rest of the city. However,

less than 1 inch of rain caused Roselle Street to flood with two feet of

water, stranding motorists who had to be rescued from their trapped vehicles.

This event is called a 1-year rain

event, since this is the amount of rain you would expect every year. In

1995, rains equivalent to a 10-year event (an event expected to occur an

average of once every 10 years - you get the idea) considered a moderate

rain event caused serious flooding in the interiors of buildings. The resulting

damage cost flooded businesses millions of dollars. One company went out

of business and is suing the City for not preventing the flooding. This event is called a 1-year rain

event, since this is the amount of rain you would expect every year. In

1995, rains equivalent to a 10-year event (an event expected to occur an

average of once every 10 years - you get the idea) considered a moderate

rain event caused serious flooding in the interiors of buildings. The resulting

damage cost flooded businesses millions of dollars. One company went out

of business and is suing the City for not preventing the flooding.

Rail transportation was halted through

the area because of the flooding. Auto traffic had to be rerouted from one

of the busiest intersections in the city. The railroad tracks are often

under water during the bigger events, requiring a railroad person to walk

in front of the trains to be sure the bridges over the creek are still there! Rail transportation was halted through

the area because of the flooding. Auto traffic had to be rerouted from one

of the busiest intersections in the city. The railroad tracks are often

under water during the bigger events, requiring a railroad person to walk

in front of the trains to be sure the bridges over the creek are still there!

Flooding during light rain events

such as those of this past year is ridiculous. Why is it happening? Four

factors are at cause: bad land use decisions, urbanization of the watershed,

channelization, and lack of maintenance. All contribute to the history of

flooding in this area. Flooding during light rain events

such as those of this past year is ridiculous. Why is it happening? Four

factors are at cause: bad land use decisions, urbanization of the watershed,

channelization, and lack of maintenance. All contribute to the history of

flooding in this area.

|

Problem #1: Flood plain development

|

| |

To put it simply, the Sorrento West

Business Park was built in a flood plain. Poor land use decisions by the

City of San Diego allowed building in this flood plain (and others, such

as the Tijuana River Valley). To put it simply, the Sorrento West

Business Park was built in a flood plain. Poor land use decisions by the

City of San Diego allowed building in this flood plain (and others, such

as the Tijuana River Valley).

Legally, the City justifies permitting

this building by saying that these flood plains weren't officially mapped

by the Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) or the Federal Emergency Management

Agency. This is technically true: the ACOE didn't officially map the area

until 1967. The maps show the "intermediate regional flood" (100-year

flood) and the "lesser flood" (50-year flood) areas for Soledad

Canyon, Carmel Valley, Los Peñasquitos Creek, Poway Creek, Rattlesnake

Creek, and Pomerado Valley, the watershed of Los Peñasquitos Lagoon. Legally, the City justifies permitting

this building by saying that these flood plains weren't officially mapped

by the Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) or the Federal Emergency Management

Agency. This is technically true: the ACOE didn't officially map the area

until 1967. The maps show the "intermediate regional flood" (100-year

flood) and the "lesser flood" (50-year flood) areas for Soledad

Canyon, Carmel Valley, Los Peñasquitos Creek, Poway Creek, Rattlesnake

Creek, and Pomerado Valley, the watershed of Los Peñasquitos Lagoon.

Truly, determining the extent of

the flood plain can sometimes be difficult. However, this is not the case

in Sorrento Valley. City planners had to know they were permitting development

in a flood-prone plain. After publication of the ACOE report, some of the

future developments were required to build on higher pads, theoretically

lifting them out of the flood plain. However, the streets surrounding them

were still below flood plain level, leaving buildings surrounded by floodwaters

. Truly, determining the extent of

the flood plain can sometimes be difficult. However, this is not the case

in Sorrento Valley. City planners had to know they were permitting development

in a flood-prone plain. After publication of the ACOE report, some of the

future developments were required to build on higher pads, theoretically

lifting them out of the flood plain. However, the streets surrounding them

were still below flood plain level, leaving buildings surrounded by floodwaters

.

Even back in 1967, ACOE noted that

floodwaters overtop the channels and cause damage to residential and commercial

development or to property suitable for such development. "The existing

flood-control works in Los Peñasquitos area are inadequate for large

flows." The report noted that these conditions existed for all six

of the creeks they studied in the drainage area. Even back in 1967, ACOE noted that

floodwaters overtop the channels and cause damage to residential and commercial

development or to property suitable for such development. "The existing

flood-control works in Los Peñasquitos area are inadequate for large

flows." The report noted that these conditions existed for all six

of the creeks they studied in the drainage area.

|

Problem #2: Urbanization

|

| |

The ACOE report was prompted by a

request from the City of San Diego, as planners looked at the plans for

future development, i.e., urbanization of the watershed. Ironically, in

1967, it was the City of Poway that was undergoing the rapid development,

while development in Mira Mesa and Carmel Valley was still a gleam in developers'

eyes. The ACOE report was prompted by a

request from the City of San Diego, as planners looked at the plans for

future development, i.e., urbanization of the watershed. Ironically, in

1967, it was the City of Poway that was undergoing the rapid development,

while development in Mira Mesa and Carmel Valley was still a gleam in developers'

eyes.

Urbanization has a big impact on

a watershed. As you convert natural lands or agricultural lands to rooftops,

parking lots and streets (impervious surfaces), you reduce the capacity

of a watershed to absorb water. The resulting runoff is carried via storm

drains into our canyons not into our sewer system and safely out to the

ocean as many people assume. As urbanization progresses, the water flow

into the canyons far exceeds historic levels. Urbanization has a big impact on

a watershed. As you convert natural lands or agricultural lands to rooftops,

parking lots and streets (impervious surfaces), you reduce the capacity

of a watershed to absorb water. The resulting runoff is carried via storm

drains into our canyons not into our sewer system and safely out to the

ocean as many people assume. As urbanization progresses, the water flow

into the canyons far exceeds historic levels.

One impact is an increase in peak

flood flows. Prestegaard estimated that the 2-year flood volume would double

on major streams, and increase by four times on urbanized tributary streams.

Similarly, a 100-year flood volume would increase by 1.3 times on major

streams and by 3 times on tributaries (Prestegaard 1975). In the same report,

Prestegaard studied the channels throughout the watershed and stated unequivocally

that, "The channel in Soledad Valley [the old name for Sorrento Valley]

cannot contain any but the lowest flows." One impact is an increase in peak

flood flows. Prestegaard estimated that the 2-year flood volume would double

on major streams, and increase by four times on urbanized tributary streams.

Similarly, a 100-year flood volume would increase by 1.3 times on major

streams and by 3 times on tributaries (Prestegaard 1975). In the same report,

Prestegaard studied the channels throughout the watershed and stated unequivocally

that, "The channel in Soledad Valley [the old name for Sorrento Valley]

cannot contain any but the lowest flows."

A 1992 San Diego Association of Governments

(SANDAG) report came to similar conclusions. This report also predicted

that the Sorrento Creek channelization could carry only a 15-year flood

peak event with urban development in place. Other impacts expected from

urbanization in our drainage have been well studied and include: increased

erosion (especially during the construction phase), increased sediment load

and declining water quality due to pollution in urban runoff pollution. A 1992 San Diego Association of Governments

(SANDAG) report came to similar conclusions. This report also predicted

that the Sorrento Creek channelization could carry only a 15-year flood

peak event with urban development in place. Other impacts expected from

urbanization in our drainage have been well studied and include: increased

erosion (especially during the construction phase), increased sediment load

and declining water quality due to pollution in urban runoff pollution.

|

Problem #3: Channelization

|

| |

So, we not only have buildings directly

in the flood plain throughout all of the creeks in the watershed, but we

also have large-scale urbanization that increases the volume and frequency

of flooding. Historically, the reaction to this threat has been to dam,

dike and channelize our rivers and streams, whether a flow is as large as

the Mississippi or as small as Peñasquitos Creek and its tributaries.

All of this has been done to these creeks. So, we not only have buildings directly

in the flood plain throughout all of the creeks in the watershed, but we

also have large-scale urbanization that increases the volume and frequency

of flooding. Historically, the reaction to this threat has been to dam,

dike and channelize our rivers and streams, whether a flow is as large as

the Mississippi or as small as Peñasquitos Creek and its tributaries.

All of this has been done to these creeks.

The idea is to take the natural stream

beds and deepen them, widen them and, often, line them with concrete or

rip rap (large rocks). Sometimes, the entire stream bed is put inside a

culvert to carry the water out to the ocean fast. This works in many cases

if you build it big enough for your biggest flood event, maintain the dikes

or channel walls, and keep them clean of debris, silt and vegetation. Ironically,

such channelization is often done on a piecemeal basis, as is the case in

our drainage. The idea is to take the natural stream

beds and deepen them, widen them and, often, line them with concrete or

rip rap (large rocks). Sometimes, the entire stream bed is put inside a

culvert to carry the water out to the ocean fast. This works in many cases

if you build it big enough for your biggest flood event, maintain the dikes

or channel walls, and keep them clean of debris, silt and vegetation. Ironically,

such channelization is often done on a piecemeal basis, as is the case in

our drainage.

Many of the tributaries in the City

of Poway that feed Peñasquitos Creek are channelized. This sends

more water downstream faster, increasing peak flows and the tendency to

flood! It's a way of exporting your flooding problem downstream. (A San

Diego city engineer recently complained in a meeting I attended that it

was impossible to get the City of Poway to return calls on this subject.) Many of the tributaries in the City

of Poway that feed Peñasquitos Creek are channelized. This sends

more water downstream faster, increasing peak flows and the tendency to

flood! It's a way of exporting your flooding problem downstream. (A San

Diego city engineer recently complained in a meeting I attended that it

was impossible to get the City of Poway to return calls on this subject.)

|

Problem #4: Maintenance

|

| |

Our fourth and last factor is the

lack of maintenance. As with many other things in our city (e.g., sewers,

roads), maintenance of channels is often the first thing to be cut in the

City budget, deferred to the "future." The result is crisis management.

The channels approaching and in Sorrento Valley were inadequately maintained

for decades. Silt carried by the increased erosion due to urbanization in

the watershed built up to a depth of 12 feet in some areas. This new land

was colonized by native and exotic plants such as arundo donax (giant

reed). The latter is well-known for clogging channels. The buildup of vegetation,

in turn, traps more sediment and slows down flood waters just where they

were meant to pass quickly. Flooding increases. Our fourth and last factor is the

lack of maintenance. As with many other things in our city (e.g., sewers,

roads), maintenance of channels is often the first thing to be cut in the

City budget, deferred to the "future." The result is crisis management.

The channels approaching and in Sorrento Valley were inadequately maintained

for decades. Silt carried by the increased erosion due to urbanization in

the watershed built up to a depth of 12 feet in some areas. This new land

was colonized by native and exotic plants such as arundo donax (giant

reed). The latter is well-known for clogging channels. The buildup of vegetation,

in turn, traps more sediment and slows down flood waters just where they

were meant to pass quickly. Flooding increases.

The lack of maintenance also meant

that storm drains from Roselle Street that emptied into Sorrento Creek were

blocked by the silt buildup. The result: flooding in light to moderate rain

events. The water in Sorrento Valley literally had no place to go and created

a lake during each moderate rainfall. The lack of maintenance also meant

that storm drains from Roselle Street that emptied into Sorrento Creek were

blocked by the silt buildup. The result: flooding in light to moderate rain

events. The water in Sorrento Valley literally had no place to go and created

a lake during each moderate rainfall.

|

Environmental concerns

|

| |

The Friends of Peñasquitos

Canyon have two sets of concerns connected to this flooding and attempts

to correct it. First, the only wildlife corridor connection from Torrey

Pines State Park to the outside natural world in this case, Peñasquitos

Canyon Preserve is along Peñasquitos Creek, from its junction with

Sorrento Creek upstream under the I-5/I-805 merge. This connection is vital

for the biological health of the wildlife in both parks. Bulldozing these

creeks will adversely impact this connection. The Friends of Peñasquitos

Canyon have two sets of concerns connected to this flooding and attempts

to correct it. First, the only wildlife corridor connection from Torrey

Pines State Park to the outside natural world in this case, Peñasquitos

Canyon Preserve is along Peñasquitos Creek, from its junction with

Sorrento Creek upstream under the I-5/I-805 merge. This connection is vital

for the biological health of the wildlife in both parks. Bulldozing these

creeks will adversely impact this connection.

In meetings with other environmental

groups (Audubon, Surfrider), Sorrento West businesses, State Parks and City

Engineering, the Friends pushed to save the wildlife corridor connection

by reducing the proposed bulldozing. Originally, the City proposed a new

pilot channel to the ocean that would be 200 feet wide in Sorrento Valley.

This would have destroyed the wildlife linkage. Facing stiff opposition

from many quarters, the City brought forward a new plan calling for a 100-foot-wide

channel in Sorrento Creek. This new plan leaves an adequate, heavily vegetated

corridor along the natural creek to the east. In meetings with other environmental

groups (Audubon, Surfrider), Sorrento West businesses, State Parks and City

Engineering, the Friends pushed to save the wildlife corridor connection

by reducing the proposed bulldozing. Originally, the City proposed a new

pilot channel to the ocean that would be 200 feet wide in Sorrento Valley.

This would have destroyed the wildlife linkage. Facing stiff opposition

from many quarters, the City brought forward a new plan calling for a 100-foot-wide

channel in Sorrento Creek. This new plan leaves an adequate, heavily vegetated

corridor along the natural creek to the east.

It's my opinion, shared by the Friend's

Tracking Team/Wildlife Survey leader and a wildlife biologist who just completed

a study for the State Park, that the bulldozing of the bottom of Peñasquitos

Creek, lowering the silt level and reducing the cattail density, can actually

improve wildlife movement through that portion of the creek. Currently,

the high silt and vegetation buildup, especially the arundo donax,

blocks wildlife movement in the area. The key is maintaining brush cover

on the two banks for the wildlife. It's my opinion, shared by the Friend's

Tracking Team/Wildlife Survey leader and a wildlife biologist who just completed

a study for the State Park, that the bulldozing of the bottom of Peñasquitos

Creek, lowering the silt level and reducing the cattail density, can actually

improve wildlife movement through that portion of the creek. Currently,

the high silt and vegetation buildup, especially the arundo donax,

blocks wildlife movement in the area. The key is maintaining brush cover

on the two banks for the wildlife.

Second, we are concerned with the

impacts of urbanization in both Parks. Erosion is a serious problem in Peñasquitos

Canyon, threatening already endangered plants (monardella linoides viminea)

and wiping out all vegetation in portions of drainages (especially López

Canyon). Increased flows and erosion are causing accelerated incising of

the creek, with headward erosion and dewatering of the associated wetlands. Second, we are concerned with the

impacts of urbanization in both Parks. Erosion is a serious problem in Peñasquitos

Canyon, threatening already endangered plants (monardella linoides viminea)

and wiping out all vegetation in portions of drainages (especially López

Canyon). Increased flows and erosion are causing accelerated incising of

the creek, with headward erosion and dewatering of the associated wetlands.

Erosion also means too much silt

gets carried downstream where it clogs the channels, as well as causing

a buildup in Peñasquitos Lagoon, creating upland habitat in place

of saltwater marsh. Runoff pollution from development ringing the Preserve

reduces our water quality to "fair" in water quality testing the

Friends and various agencies have conducted. For instance, too many nutrients

and too much nitrogen and phosphorus in the water promotes a buildup of

algae and "algal blooms," to the detriment of fish and benthic

organisms. Erosion also means too much silt

gets carried downstream where it clogs the channels, as well as causing

a buildup in Peñasquitos Lagoon, creating upland habitat in place

of saltwater marsh. Runoff pollution from development ringing the Preserve

reduces our water quality to "fair" in water quality testing the

Friends and various agencies have conducted. For instance, too many nutrients

and too much nitrogen and phosphorus in the water promotes a buildup of

algae and "algal blooms," to the detriment of fish and benthic

organisms.

This situation is exacerbated by

the inadequate tidal flushing in the lagoon, due to the closing of the mouth

of the lagoon by various highways and bridges crossing it. With the mouth

closed and too many nutrients and consequent algal blooms the lagoon can

quickly deplete its oxygen, leading to kill-offs of its fish and mollusk

populations. This, in turn, effects the bird populations that depend on

the lagoon for their food. This situation is exacerbated by

the inadequate tidal flushing in the lagoon, due to the closing of the mouth

of the lagoon by various highways and bridges crossing it. With the mouth

closed and too many nutrients and consequent algal blooms the lagoon can

quickly deplete its oxygen, leading to kill-offs of its fish and mollusk

populations. This, in turn, effects the bird populations that depend on

the lagoon for their food.

Urbanization also means more fresh

water all year, as well as during storm events, leading to a buildup of

freshwater habitat at the expense of salt marsh in Peñasquitos Lagoon.

Salt marsh habitat is rarer and is a priority for preservation. Urbanization also means more fresh

water all year, as well as during storm events, leading to a buildup of

freshwater habitat at the expense of salt marsh in Peñasquitos Lagoon.

Salt marsh habitat is rarer and is a priority for preservation.

|

A brief history: a creek by any other name ...

|

| |

Sorrento Valley and Sorrento Creek

are new names. Until the 1960s, they were Soledad Valley and Soledad Creek.

There is still a Soledad Canyon in the southern (upper) portion of Sorrento

Valley. It is now only a major finger canyon, running northwest to southeast

off Carroll Canyon, carrying the Santa Fe Railroad under Miramar Road and

across the Marine Air Station. (It's a beautiful canyon, with some of San

Diego's oldest coast live oaks, good habitat, mule deer, hawks, etc. It's

also a good wildlife corridor. You can access it off of Carroll Road at

Scranton.) Sorrento Valley and Sorrento Creek

are new names. Until the 1960s, they were Soledad Valley and Soledad Creek.

There is still a Soledad Canyon in the southern (upper) portion of Sorrento

Valley. It is now only a major finger canyon, running northwest to southeast

off Carroll Canyon, carrying the Santa Fe Railroad under Miramar Road and

across the Marine Air Station. (It's a beautiful canyon, with some of San

Diego's oldest coast live oaks, good habitat, mule deer, hawks, etc. It's

also a good wildlife corridor. You can access it off of Carroll Road at

Scranton.)

Peñasquitos Creek once referred

to the entire length of the creek, from the foothills of Poway all the way

into Soledad Valley. Now, the upper portion in Poway is called Poway Creek. Peñasquitos Creek once referred

to the entire length of the creek, from the foothills of Poway all the way

into Soledad Valley. Now, the upper portion in Poway is called Poway Creek.

|

Watersheds

|

| |

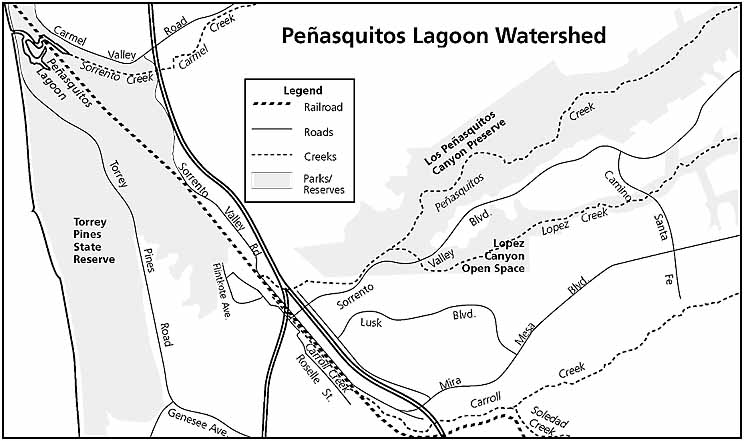

Webster's defines "watershed"

as "the area drained by a river or river system." The watershed

that drains into Peñasquitos Lagoon ranges from 95 sq. mi. (ACOE,

1967) to 98 sq. mi. (Prestegaard 1975), depending on whose estimate you

use. It includes the drainages of Carmel Valley, Carroll Canyon and Los

Peñasquitos Canyon (Peñasquitos Canyon reaches all the way

up into Poway). Webster's defines "watershed"

as "the area drained by a river or river system." The watershed

that drains into Peñasquitos Lagoon ranges from 95 sq. mi. (ACOE,

1967) to 98 sq. mi. (Prestegaard 1975), depending on whose estimate you

use. It includes the drainages of Carmel Valley, Carroll Canyon and Los

Peñasquitos Canyon (Peñasquitos Canyon reaches all the way

up into Poway).

The Peñasquitos drainage or

sub-watershed is the largest of the three, being about 58 sq. mi. The major

creeks or tributaries flowing in these drainages include Deer Canyon Creek,

which flows into Carmel Creek in Carmel Valley; Carroll Creek; and Pomerado,

Rattlesnake, and Beeler Creeks which all flow into Poway Creek, which becomes

Peñasquitos Creek. The Peñasquitos drainage or

sub-watershed is the largest of the three, being about 58 sq. mi. The major

creeks or tributaries flowing in these drainages include Deer Canyon Creek,

which flows into Carmel Creek in Carmel Valley; Carroll Creek; and Pomerado,

Rattlesnake, and Beeler Creeks which all flow into Poway Creek, which becomes

Peñasquitos Creek.

|

The insults begin

|

| |

I use insults here as both a technical

term for negative impacts on the land and water, and as a pejorative. I use insults here as both a technical

term for negative impacts on the land and water, and as a pejorative.

The first major insult to Peñasquitos

Lagoon occurred with the building of the railroad in about 1888. This began

the process of closing the lagoon mouth to the influence of the tides that

are necessary to maintain it as a healthy salt water-dominated water and

marsh habitat. The first major insult to Peñasquitos

Lagoon occurred with the building of the railroad in about 1888. This began

the process of closing the lagoon mouth to the influence of the tides that

are necessary to maintain it as a healthy salt water-dominated water and

marsh habitat.

Ellis and Lee reported in 1919 that

the "Soledad Streams" were able to keep narrow channels open through

the beach, at least during part of the year. However, the building of Highway

101 across the lagoon in 1932 worsened the situation. The lagoon began to

be closed most of the time, causing a die-off of saltwater-dependent organisms

and vegetation and a shift in the types of vegetation present. For example,

no living mollusk species were found in several studies in the 1960s. Only

during exceptionally wet winters could sufficient freshwater collect to

break through the barrier bar that develops in the lagoon mouth. Ellis and Lee reported in 1919 that

the "Soledad Streams" were able to keep narrow channels open through

the beach, at least during part of the year. However, the building of Highway

101 across the lagoon in 1932 worsened the situation. The lagoon began to

be closed most of the time, causing a die-off of saltwater-dependent organisms

and vegetation and a shift in the types of vegetation present. For example,

no living mollusk species were found in several studies in the 1960s. Only

during exceptionally wet winters could sufficient freshwater collect to

break through the barrier bar that develops in the lagoon mouth.

|

Sewage flows in creek and lagoon

|

| |

In the 1980s, our daily paper often

treated us to news of sewage spills from the infamous pump station in Peñasquitos

Lagoon, closing beaches and promoting organism die-offs. However, what most

people don't know is that treated sewage (the PR term is "treated effluent")

was intentionally pumped into the Lagoon for decades. In the 1980s, our daily paper often

treated us to news of sewage spills from the infamous pump station in Peñasquitos

Lagoon, closing beaches and promoting organism die-offs. However, what most

people don't know is that treated sewage (the PR term is "treated effluent")

was intentionally pumped into the Lagoon for decades.

The Callan Treatment plant, an old

WWII facility located on Torrey Pines Mesa, was reactivated in the 1950s

and began pumping 50,000 gallons of treated effluent per day into Soledad

Creek and the lagoon. It was joined in 1962 by the Sorrento plant, which

was pumping about 500,000 gallons per day into the same lagoon. Another

facility, the Pomerado Waste Water Treatment Plant, pumped even more treated

sewage into Peñasquitos Creek from 1962 to 1972. The Callan Treatment plant, an old

WWII facility located on Torrey Pines Mesa, was reactivated in the 1950s

and began pumping 50,000 gallons of treated effluent per day into Soledad

Creek and the lagoon. It was joined in 1962 by the Sorrento plant, which

was pumping about 500,000 gallons per day into the same lagoon. Another

facility, the Pomerado Waste Water Treatment Plant, pumped even more treated

sewage into Peñasquitos Creek from 1962 to 1972.

In addition, the Peñasquitos

Settling Ponds were used for sewage treatment, perhaps as late as 1967;

I have yet to find a good report on these. These ponds may still be seen,

vegetated now, just west of the Rancho Santa Maria ranch house off Black

Mountain Road. These 14 acres of dikes and ponds sit right next to Peñasquitos

Creek. What we don't yet know is if any of this effluent was pumped or leaked

into the creek. (This is an area the Friends hope to restore soon.) Many

folks living downstream during this period, in Mira Mesa and Rancho Peñasquitos,

had no idea the stream they were visiting and their kids were playing in

was in large part treated sewage! In addition, the Peñasquitos

Settling Ponds were used for sewage treatment, perhaps as late as 1967;

I have yet to find a good report on these. These ponds may still be seen,

vegetated now, just west of the Rancho Santa Maria ranch house off Black

Mountain Road. These 14 acres of dikes and ponds sit right next to Peñasquitos

Creek. What we don't yet know is if any of this effluent was pumped or leaked

into the creek. (This is an area the Friends hope to restore soon.) Many

folks living downstream during this period, in Mira Mesa and Rancho Peñasquitos,

had no idea the stream they were visiting and their kids were playing in

was in large part treated sewage!

Plans for an SDGE Nuclear Power Plant

in Sorrento Valley and for a new Pomerado Water Reclamation Plant with live

stream discharge were both discarded. Public opposition played a big role

in both decisions. Plans for an SDGE Nuclear Power Plant

in Sorrento Valley and for a new Pomerado Water Reclamation Plant with live

stream discharge were both discarded. Public opposition played a big role

in both decisions.

|

"Effluent" impacts on lagoon

|

| |

The discharge of treated effluent

brought two problems with it. One was fresh water flows into the lagoon

that were way above the historic levels, particularly outside of the rainy

season. This effluent flow occurred during a time when urbanization was

also adding fresh water to the system, not just during storm events, but

all year long due to irrigation. The discharge of treated effluent

brought two problems with it. One was fresh water flows into the lagoon

that were way above the historic levels, particularly outside of the rainy

season. This effluent flow occurred during a time when urbanization was

also adding fresh water to the system, not just during storm events, but

all year long due to irrigation.

The second problem was the high nitrate

and phosphate levels of the effluent. This combination of additional nutrient-rich

fresh water pouring into a closed lagoon system without adequate tidal flushing

led to repeated die-offs and the shift in vegetation types. Elevated temperatures

occur up in the waters of a closed system like this, and contribute to the

die-offs. Such a die-off occurred in San Elijo Lagoon in the summer of 1997. The second problem was the high nitrate

and phosphate levels of the effluent. This combination of additional nutrient-rich

fresh water pouring into a closed lagoon system without adequate tidal flushing

led to repeated die-offs and the shift in vegetation types. Elevated temperatures

occur up in the waters of a closed system like this, and contribute to the

die-offs. Such a die-off occurred in San Elijo Lagoon in the summer of 1997.

Another problem caused by this infusion

of effluent was a tremendous mosquito problem. This prompted significant

public opposition to these flows and, combined with studies of the negative

biological impacts, led the Regional Water Quality Control Board to oppose

continuation of these existing facilities or the building of new ones. Another problem caused by this infusion

of effluent was a tremendous mosquito problem. This prompted significant

public opposition to these flows and, combined with studies of the negative

biological impacts, led the Regional Water Quality Control Board to oppose

continuation of these existing facilities or the building of new ones.

Peñasquitos Lagoon's mouth

is now kept open with periodic and expensive bulldozing but it accomplishes

its purpose of permitting tidal flushing. Peñasquitos Lagoon's mouth

is now kept open with periodic and expensive bulldozing but it accomplishes

its purpose of permitting tidal flushing.

|

Impacts on Peñasquitos Creek

|

| |

Peñasquitos Creek is now a

perennial creek, flowing year round. Was this always the case? Firsthand

observations by various individuals, plus U.S. Geological Survey data for

the creek starting in 1964, indicate that the creek wasn't consistently

perennial. In years with above average rainfalls, heavy late seasonal rainfalls

or significant summer rain, the creek flowed to the lagoon throughout the

year. During years of average to low rain flows, certainly during periods

of extended drought, it was seasonal. This shouldn't be surprising in our

arid climate. Peñasquitos Creek is now a

perennial creek, flowing year round. Was this always the case? Firsthand

observations by various individuals, plus U.S. Geological Survey data for

the creek starting in 1964, indicate that the creek wasn't consistently

perennial. In years with above average rainfalls, heavy late seasonal rainfalls

or significant summer rain, the creek flowed to the lagoon throughout the

year. During years of average to low rain flows, certainly during periods

of extended drought, it was seasonal. This shouldn't be surprising in our

arid climate.

The flow data we do have (on the

web at www.usgs.gov) illustrates the impact of the live stream discharge

between 1962-1972. From 1965-1972, the median discharge of treated effluent

was .90 cfs (cubic feet per second), ranging from a low of .03 cfs to a

high of 3.50 cfs. It also showed a sharp drop when the plant closed in 1972.

From 1973-1979, the median discharge dropped to a low of 0.10 cfs, with

a range of 0.00 to 25 cfs. In other words, at times, there was no measurable

flow in the creek. Thereafter, the median discharge steadily increased,

even during the summer months, probably reflecting increased runoff due

to urbanization in the watershed. The flow data we do have (on the

web at www.usgs.gov) illustrates the impact of the live stream discharge

between 1962-1972. From 1965-1972, the median discharge of treated effluent

was .90 cfs (cubic feet per second), ranging from a low of .03 cfs to a

high of 3.50 cfs. It also showed a sharp drop when the plant closed in 1972.

From 1973-1979, the median discharge dropped to a low of 0.10 cfs, with

a range of 0.00 to 25 cfs. In other words, at times, there was no measurable

flow in the creek. Thereafter, the median discharge steadily increased,

even during the summer months, probably reflecting increased runoff due

to urbanization in the watershed.

The natural springs feeding Peñasquitos

Creek are too few and far between to promote a year round flow, except in

their immediate downstream areas. The largest natural spring pumps up to

86,000 gallons per day into the creek. If you were standing downstream of

one of these springs, the creek would certainly be flowing past you at any

given time, probably, but not all the way to the ocean. If you were standing

downstream in the lagoon during the period of 1950-1972, you would have

been seeing a flow but mostly of treated effluent. The natural springs feeding Peñasquitos

Creek are too few and far between to promote a year round flow, except in

their immediate downstream areas. The largest natural spring pumps up to

86,000 gallons per day into the creek. If you were standing downstream of

one of these springs, the creek would certainly be flowing past you at any

given time, probably, but not all the way to the ocean. If you were standing

downstream in the lagoon during the period of 1950-1972, you would have

been seeing a flow but mostly of treated effluent.

Now, however, we have a strong year-round

flow, even during the most recent drought, due to irrigation, car washing,

etc.. Is this additional flow good or bad? These flows do tend to bring

toxics (oil from driveways), pesticides and fertilizer all harmful to some

extent to the water and the organisms in it. However, each significant finger

canyon in the Preserve now has a new riparian area in it: this is both good

and bad. Riparian areas in the desert tend to be scarce, but extremely important

to wildlife. Adding some small acreages is beneficial. On the negative side,

this same runoff brings seeds of exotic plants, which tend to have a negative

impact on local flora and fauna. The Friends are spending considerable energies

clearing these exotics out of these same canyons. Constant management can

control the exotics. Now, however, we have a strong year-round

flow, even during the most recent drought, due to irrigation, car washing,

etc.. Is this additional flow good or bad? These flows do tend to bring

toxics (oil from driveways), pesticides and fertilizer all harmful to some

extent to the water and the organisms in it. However, each significant finger

canyon in the Preserve now has a new riparian area in it: this is both good

and bad. Riparian areas in the desert tend to be scarce, but extremely important

to wildlife. Adding some small acreages is beneficial. On the negative side,

this same runoff brings seeds of exotic plants, which tend to have a negative

impact on local flora and fauna. The Friends are spending considerable energies

clearing these exotics out of these same canyons. Constant management can

control the exotics.

The worst impact from urbanization,

I feel, is the increase in peak flow and velocity during storms. We are

seeing much more erosion, areas that are denuded and remain so, and beds

of cobble or bedrock with no vegetation. The Friends are still grappling

with how to mitigate this problem. The worst impact from urbanization,

I feel, is the increase in peak flow and velocity during storms. We are

seeing much more erosion, areas that are denuded and remain so, and beds

of cobble or bedrock with no vegetation. The Friends are still grappling

with how to mitigate this problem.

|

Mitigation

|

| |

When their projects impact salt marsh

and fresh water riparian areas, the City is required to mitigate by restoring

or creating similar habitat elsewhere. As mitigation for the creek bulldozing,

a proposal to remove old dikes, restoring the historic flood plain, was

accepted, and restoring wetlands was tentatively accepted. This is the area

we call the "bean fields," north and east of the El Cuervo adobe

ruins at the Sorrento Valley end of the Preserve. Detailed analysis and

plans are being worked up. We wanted this proposal to emphasize the need

for upstream solutions - where the problems originate - and solutions that

deal with the underlying causes of the flooding and the negative impacts

on the lagoon. When their projects impact salt marsh

and fresh water riparian areas, the City is required to mitigate by restoring

or creating similar habitat elsewhere. As mitigation for the creek bulldozing,

a proposal to remove old dikes, restoring the historic flood plain, was

accepted, and restoring wetlands was tentatively accepted. This is the area

we call the "bean fields," north and east of the El Cuervo adobe

ruins at the Sorrento Valley end of the Preserve. Detailed analysis and

plans are being worked up. We wanted this proposal to emphasize the need

for upstream solutions - where the problems originate - and solutions that

deal with the underlying causes of the flooding and the negative impacts

on the lagoon. |

City stonewalling

|

|

In the meetings with the City Engineering

Dept., The Friends and others emphasized the importance of looking at the

flooding and other problems we have identified as watershed problems. We

argued for upstream solutions to reduce the siltation and peak flows that

cause downstream problems. We argued that this would be safer and cheaper

for the taxpayers in the long run, in place of the crisis management of

the past. In the meetings with the City Engineering

Dept., The Friends and others emphasized the importance of looking at the

flooding and other problems we have identified as watershed problems. We

argued for upstream solutions to reduce the siltation and peak flows that

cause downstream problems. We argued that this would be safer and cheaper

for the taxpayers in the long run, in place of the crisis management of

the past.

Unfortunately, we did not feel that

the City was responsive to this perspective, in any way. We will keep pushing

this perspective. It's the right thing to do. Unfortunately, we did not feel that

the City was responsive to this perspective, in any way. We will keep pushing

this perspective. It's the right thing to do.

Reprinted from Canyon News, the newsletter of the Friends of Los Peñasquitos

Canyon Preserve, Inc., with permission. To find out about memberships, call

(619) 484-3219 or (619) 566-6489. To find out about volunteering to help

with their ongoing preservation and restoration projects, call 619) 224-4192. Reprinted from Canyon News, the newsletter of the Friends of Los Peñasquitos

Canyon Preserve, Inc., with permission. To find out about memberships, call

(619) 484-3219 or (619) 566-6489. To find out about volunteering to help

with their ongoing preservation and restoration projects, call 619) 224-4192.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()