Horticulturally correct

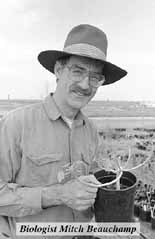

Every day we waste precious water caring for vegetation inappropriate

to our environment. Mitch Beauchamp is out to do something about it.

by Jack Innis

tretched between San Miguel and Otay Mountain, at an

altitude of precisely 524 feet, is a nightmarish canvas of misused earth

named Otay Mesa. The mesa has been scarred by decades of men with yellow

tractors and senseless dreams who have leveled, tiered, gored, and rutted

in her dark brown soil, then abandoned her like a poacher's kill.

tretched between San Miguel and Otay Mountain, at an

altitude of precisely 524 feet, is a nightmarish canvas of misused earth

named Otay Mesa. The mesa has been scarred by decades of men with yellow

tractors and senseless dreams who have leveled, tiered, gored, and rutted

in her dark brown soil, then abandoned her like a poacher's kill.

Amid the mishmash atop the mesa - the prison, the junkyards,

the $81 per-month offices, the airport, and warehouses - on Cactus Road,

precisely 2 1/2 miles south of Otay Mesa Road, lies Pacific Southwest Nurseries.

In an unassuming trailer on the edge of the nursery is the office of noted

botanist Mitch Beauchamp, the man who salves the wounds inflicted upon the

earth by mankind.

Amid the mishmash atop the mesa - the prison, the junkyards,

the $81 per-month offices, the airport, and warehouses - on Cactus Road,

precisely 2 1/2 miles south of Otay Mesa Road, lies Pacific Southwest Nurseries.

In an unassuming trailer on the edge of the nursery is the office of noted

botanist Mitch Beauchamp, the man who salves the wounds inflicted upon the

earth by mankind.

Mitch Beauchamp (pronounced Beecham) owns Pacific Southwest

Biological Surveys, a company dedicated to restoring precious wetland and

upland habitats. The nursery is an important part of his operations, supplying

plants for Southern California revegetation.

Mitch Beauchamp (pronounced Beecham) owns Pacific Southwest

Biological Surveys, a company dedicated to restoring precious wetland and

upland habitats. The nursery is an important part of his operations, supplying

plants for Southern California revegetation.

What is special to San Diegans is that Beauchamp utilizes

native and xeriscape plants - plants that thrive on very little water and

attention.

What is special to San Diegans is that Beauchamp utilizes

native and xeriscape plants - plants that thrive on very little water and

attention.

"Xeriscape means dry," said Beauchamp recently,

on a muggy day at his fifteen-acre nursery. "I call it 'appropriate

horticulture', plants that are adapted to this climate. Once established,

they don't need irrigation. Because a lot of them don't grow very fast,

you don't need to prune them or fertilize them."

"Xeriscape means dry," said Beauchamp recently,

on a muggy day at his fifteen-acre nursery. "I call it 'appropriate

horticulture', plants that are adapted to this climate. Once established,

they don't need irrigation. Because a lot of them don't grow very fast,

you don't need to prune them or fertilize them."

Beauchamp's list of consulting projects includes salt-marsh

restoration at the Silver Strand in Coronado, Agua Hedionda in Carlsbad,

and Gunpowder Point in Chula Vista. He has also planted eelgrass at Delta

Beach near the naval amphibian base at Coronado, provided willow habitat

in the Otay Valley for the Cal-Amerlcan Pipeline, and has done several projects

in North County. His very first project was the Sweetwater River Channel

in 1970, completed just last year by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers.

Beauchamp's list of consulting projects includes salt-marsh

restoration at the Silver Strand in Coronado, Agua Hedionda in Carlsbad,

and Gunpowder Point in Chula Vista. He has also planted eelgrass at Delta

Beach near the naval amphibian base at Coronado, provided willow habitat

in the Otay Valley for the Cal-Amerlcan Pipeline, and has done several projects

in North County. His very first project was the Sweetwater River Channel

in 1970, completed just last year by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers.

Surprisingly, not all of the plants Beauchamp uses are

native to California or even North America.

Surprisingly, not all of the plants Beauchamp uses are

native to California or even North America.

"Our focus is horticulturally appropriate plant

material," Beauchamp said. "That means plants adapted to what

is called a Mediterranean climate: cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers.

Some native plants, especially those from Northern California, are inappropriate

in Southern California. There are other species from Australia, Chili, South

Africa and the Mediterranean region that are better adapted."

"Our focus is horticulturally appropriate plant

material," Beauchamp said. "That means plants adapted to what

is called a Mediterranean climate: cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers.

Some native plants, especially those from Northern California, are inappropriate

in Southern California. There are other species from Australia, Chili, South

Africa and the Mediterranean region that are better adapted."

Beauchamp is concerned that developers begin using the

correct plants. On this he is adamant:

Beauchamp is concerned that developers begin using the

correct plants. On this he is adamant:

"One of Southern California's biggest problems is to get landscape

architects to specify horticulturally appropriate plants. They are totally

ignorant of plant materials. They come out of Cal-Poly or wherever with

one course in plant materials and the don't specify the appropriate plants."

Beauchamp pointed to a display where he keeps ten each

of his horticulturally appropriate plants. Natives such as wild lilacs,

mint, bayberry and golden yarrow are mingled with malvarosa from Mexico's

Los Coronados Islands and Bunya-Bunya trees from Queensland, Australia.

Beauchamp pointed to a display where he keeps ten each

of his horticulturally appropriate plants. Natives such as wild lilacs,

mint, bayberry and golden yarrow are mingled with malvarosa from Mexico's

Los Coronados Islands and Bunya-Bunya trees from Queensland, Australia.

While some of his plants are thorny and more suitable

as barrier plants, others, such as the lemonade berry, could take center

stage in any garden. Their common feature is the ability to flourish with

little attention and even less water. In the semiarid desert conditions

of Southern California, low water usage is becoming more important every

day.

While some of his plants are thorny and more suitable

as barrier plants, others, such as the lemonade berry, could take center

stage in any garden. Their common feature is the ability to flourish with

little attention and even less water. In the semiarid desert conditions

of Southern California, low water usage is becoming more important every

day.

"One of our botanists is working with homeowners'

associations to develop retrofits," Beauchamp said. Homeowners' associations

are looking toward alternative landscaping as a means to fight ever increasing

water bills. A good example is a property in Orange County. The homeowner's

association has a water bill of $17,000 per month for a 30-acre slope. One

phase of the project, which has yet to be built, is called MiraSol and happens

to be the home of the gnatcatcher. Because of the gnatcatcher the developer

cannot disturb the slope. Without the gnatcatcher the developer would have

to landscape because that's what the people in the city think they want.

"One of our botanists is working with homeowners'

associations to develop retrofits," Beauchamp said. Homeowners' associations

are looking toward alternative landscaping as a means to fight ever increasing

water bills. A good example is a property in Orange County. The homeowner's

association has a water bill of $17,000 per month for a 30-acre slope. One

phase of the project, which has yet to be built, is called MiraSol and happens

to be the home of the gnatcatcher. Because of the gnatcatcher the developer

cannot disturb the slope. Without the gnatcatcher the developer would have

to landscape because that's what the people in the city think they want.

"What we've done is to install

a wall and a watering system that moistens the area, but does not irrigate

it. The expected water bill for the site is expected to be about $50, compared

to $17,000 for MiraSol's other slope. The only difference is a modification

that has to be done every three or four years to reduce flammability. But

the bird is there, the vegetation is there, and the erosion control is there.

It just doesn't have iceplant that flowers every fall."

"What we've done is to install

a wall and a watering system that moistens the area, but does not irrigate

it. The expected water bill for the site is expected to be about $50, compared

to $17,000 for MiraSol's other slope. The only difference is a modification

that has to be done every three or four years to reduce flammability. But

the bird is there, the vegetation is there, and the erosion control is there.

It just doesn't have iceplant that flowers every fall."

Although the water-saving plants Beauchamp grows are

for sale to the public at his nursery, he warns drive-up customers not to

expect the same level of service they find at NurseryLand.

Although the water-saving plants Beauchamp grows are

for sale to the public at his nursery, he warns drive-up customers not to

expect the same level of service they find at NurseryLand.

"We are a very odd company because we're a bunch

of botanists. We're not nurserymen and we don't hold hands here. If a customer

knows what they want and brings it up we'll write up the ticket, they pay

for it and drive away. We do not offer advise unless we set up a consulting

contract and go to their house and put together a package for their needs."

"We are a very odd company because we're a bunch

of botanists. We're not nurserymen and we don't hold hands here. If a customer

knows what they want and brings it up we'll write up the ticket, they pay

for it and drive away. We do not offer advise unless we set up a consulting

contract and go to their house and put together a package for their needs."

While consulting to individual homeowners is rare because

of the high costs involved ($2,000 plus material), the high water rates

in Southern California may make homeowner contacts more frequent.

While consulting to individual homeowners is rare because

of the high costs involved ($2,000 plus material), the high water rates

in Southern California may make homeowner contacts more frequent.

"We do get calls from time to time," he said, "mainly from

people in La Jolla or Rancho Bernardo - people who know the value of a dollar.

We're even trying to find a substitute for turf. Our feeling is, if you're

not playing football or croquet with your kids on it, why have a lawn?"

"Most developers," Beauchamp said, "would

like to pave San Diego from the seashore to the mountains."

"Most developers," Beauchamp said, "would

like to pave San Diego from the seashore to the mountains."

Mitch Beauchamp would like to plant San Diego from the

seashore to the mountains - with horticulturally appropriate vegetation.

Mitch Beauchamp would like to plant San Diego from the

seashore to the mountains - with horticulturally appropriate vegetation.

Jack Innis is a freelance writer. More than 40 of his outdoor and

environmental articles have been published nationwide.