Tijuana River: a controversy runs through it

On a spring afternoon, the Tijuana River Valley appears tranquil. Wildflowers

perfume the air. Hawks hover a few feet over the ground, hunting in the

salt marsh. Horseback riders amble down narrow roads. Only the U.S. Border

Patrol driving 4x4's, trying in vain to stem the tide of illegal immigrants

flowing in from Mexico, seem to be in a hurry.

by Lori Saldaña

he valley lies immediately north of the U.S.-Mexico

border, between San Ysidro and Interstate 5 to the east, the Pacific Ocean

to the west, and pushed up against the tract homes and suburban spread of

Imperial Beach and Nestor to the north. The river running through this broad,

green landscape receives its water from creeks, streams and other small

tributaries draining some 1,700 square miles. More than 70% of that land

is in Mexico.

he valley lies immediately north of the U.S.-Mexico

border, between San Ysidro and Interstate 5 to the east, the Pacific Ocean

to the west, and pushed up against the tract homes and suburban spread of

Imperial Beach and Nestor to the north. The river running through this broad,

green landscape receives its water from creeks, streams and other small

tributaries draining some 1,700 square miles. More than 70% of that land

is in Mexico.

The river crosses the international border east of Interstate

5 and meanders northwest for about five miles before reaching the ocean.

A land ownership map of this region looks like a patchwork quilt. The river

winds its way thought lots owned by private parties, the city and county

of San Diego, and various state and federal resource agencies, including

the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the California Department of Fish

and Game.

The river crosses the international border east of Interstate

5 and meanders northwest for about five miles before reaching the ocean.

A land ownership map of this region looks like a patchwork quilt. The river

winds its way thought lots owned by private parties, the city and county

of San Diego, and various state and federal resource agencies, including

the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the California Department of Fish

and Game.

The valley covers 3,000 acres and includes some of the

last undeveloped coastal wetlands in San Diego County.

The valley covers 3,000 acres and includes some of the

last undeveloped coastal wetlands in San Diego County.

Disappearing wetlands

Statewide, less than 10 percent of native wetlands still

exist. Most of the state's original estuaries (partially enclosed coastal

bodies of water filled with a mix of rain, river water and salty ocean tides)

and their surrounding vegetation communities (known as salt marshes) have

been lost to dredging and development. This practice has created deep-water

harbors such as San Diego Bay, and recreational parks and marinas, such

as Mission Bay.

Statewide, less than 10 percent of native wetlands still

exist. Most of the state's original estuaries (partially enclosed coastal

bodies of water filled with a mix of rain, river water and salty ocean tides)

and their surrounding vegetation communities (known as salt marshes) have

been lost to dredging and development. This practice has created deep-water

harbors such as San Diego Bay, and recreational parks and marinas, such

as Mission Bay.

Many of the natural estuaries that remain, such as the

city-owned Famosa Slough in the Loma Portal area, have been placed in permanent

reserves to prevent further loss. The Tijuana River's estuary has been permanently

protected under the National Estuarine Sanctuaries program.

Many of the natural estuaries that remain, such as the

city-owned Famosa Slough in the Loma Portal area, have been placed in permanent

reserves to prevent further loss. The Tijuana River's estuary has been permanently

protected under the National Estuarine Sanctuaries program.

Other parts of the river valley, upstream of the estuary,

are still subject to a variety of uses and development. These include sand

dredging and gravel mining operations, horse boarding stables and agricultural

operations.

Other parts of the river valley, upstream of the estuary,

are still subject to a variety of uses and development. These include sand

dredging and gravel mining operations, horse boarding stables and agricultural

operations.

The loss of wetlands throughout the state has meant

the loss of critical habitat for native fish, birds, mammals, and plants.

Still, as one drives into the Tijuana River Valley, there are no obvious

indications of its biological importance. The only signs posted at the entrance

along Dairy Mart Road - printed in both English and Spanish - warn against

illegal dumping. Less than a mile away, in violation of these signs, 50-gallon

drums and stripped car chassis lie rusting along the road.

The loss of wetlands throughout the state has meant

the loss of critical habitat for native fish, birds, mammals, and plants.

Still, as one drives into the Tijuana River Valley, there are no obvious

indications of its biological importance. The only signs posted at the entrance

along Dairy Mart Road - printed in both English and Spanish - warn against

illegal dumping. Less than a mile away, in violation of these signs, 50-gallon

drums and stripped car chassis lie rusting along the road.

Several miles west, near the entrance to Border Field

State park at the southern edge of the estuary, one finally finds interpretive

signs and maps explaining the importance of wetlands. Beneath an illustration

of a salt marsh is the following message: "If we destroy our remaining

coastal wetlands ... we would lose an important source of food. Two-thirds

of fish and shellfish found in coastal waters and eaten by humans spend

part of their lives in estuaries such as this one.

Several miles west, near the entrance to Border Field

State park at the southern edge of the estuary, one finally finds interpretive

signs and maps explaining the importance of wetlands. Beneath an illustration

of a salt marsh is the following message: "If we destroy our remaining

coastal wetlands ... we would lose an important source of food. Two-thirds

of fish and shellfish found in coastal waters and eaten by humans spend

part of their lives in estuaries such as this one.

"Finally, we would lose the myriad plants and animals

that live in the wetlands and that enhance our sense of the quiet beauty

of nature. By preserving marsh habitats we protect our quality of life and

well being - the spark of wildness that exists in us all."

"Finally, we would lose the myriad plants and animals

that live in the wetlands and that enhance our sense of the quiet beauty

of nature. By preserving marsh habitats we protect our quality of life and

well being - the spark of wildness that exists in us all."

It's a powerful message - but no one seems to be listening.

It's a powerful message - but no one seems to be listening.

Overflows and floods

Despite these warnings, population increases and the

resulting development in both the United States and Mexico have created

problems in the valley, its estuary and the Pacific Ocean. More than 1.2

million people live in the city of San Diego, and an estimated 2 million

people live in Tijuana. During the previous 10 years, Tijuana's population

has substantially exceeded its sewage system capacity.

Despite these warnings, population increases and the

resulting development in both the United States and Mexico have created

problems in the valley, its estuary and the Pacific Ocean. More than 1.2

million people live in the city of San Diego, and an estimated 2 million

people live in Tijuana. During the previous 10 years, Tijuana's population

has substantially exceeded its sewage system capacity.

As a result, raw sewage mixed with industrial and agricultural

wastes regularly overflows into the canyons surrounding the city. These

canyons carry the flows across the international border and into the United

States, along the southern edge of the valley. The wastewater flows into

the river, contaminating the estuary, and occasionally forcing beach closures.

As a result, raw sewage mixed with industrial and agricultural

wastes regularly overflows into the canyons surrounding the city. These

canyons carry the flows across the international border and into the United

States, along the southern edge of the valley. The wastewater flows into

the river, contaminating the estuary, and occasionally forcing beach closures.

Besides contaminating the valley, these excess sewage

flows have become expensive to manage. A 1993 report from the San Diego

City Manager's office reports that, since October 1991, the city had collected

an average of 13 millions gallons of Mexican sewage per day. The sewage

is treated at the Point Loma wastewater plant at a cost to the city and

state of nearly $500,000 per month.

Besides contaminating the valley, these excess sewage

flows have become expensive to manage. A 1993 report from the San Diego

City Manager's office reports that, since October 1991, the city had collected

an average of 13 millions gallons of Mexican sewage per day. The sewage

is treated at the Point Loma wastewater plant at a cost to the city and

state of nearly $500,000 per month.

Flooding during heavy winter storms has also been a

problem. In the 1970s, Mexico constructed a concrete channel to control

flooding through Tijuana, but the channel ends at the border. Its planned

connector on the U.S. side has never been completed due to concerns over

destroying habitat for endangered species, including birds such as the least

Bell's vireo, light-footed clapper rail, and California least tern.

Flooding during heavy winter storms has also been a

problem. In the 1970s, Mexico constructed a concrete channel to control

flooding through Tijuana, but the channel ends at the border. Its planned

connector on the U.S. side has never been completed due to concerns over

destroying habitat for endangered species, including birds such as the least

Bell's vireo, light-footed clapper rail, and California least tern.

Throughout most of the 1980s, Southern California experienced

extremely dry winters. But in 1993, the combination of heavy winter storms,

overgrown vegetation, illegally constructed berms and piles of fill dirt

caused winter floodwaters to shift the river's course, destroy a bridge,

and flood neighborhoods to the north for the first time.

Throughout most of the 1980s, Southern California experienced

extremely dry winters. But in 1993, the combination of heavy winter storms,

overgrown vegetation, illegally constructed berms and piles of fill dirt

caused winter floodwaters to shift the river's course, destroy a bridge,

and flood neighborhoods to the north for the first time.

Plans for survival

Today, few obvious signs of the floods of 1993 remain

in the valley. The waters have receded, and a temporary Bailey bridge has

replaced the one destroyed by the high waters. Its single lane now carries

cars into the valley, crossing the river along Hollister Street. At night,

the sounds of flowing water, frog calls and buzzing insects fill the air;

owls fly silently overhead.

Today, few obvious signs of the floods of 1993 remain

in the valley. The waters have receded, and a temporary Bailey bridge has

replaced the one destroyed by the high waters. Its single lane now carries

cars into the valley, crossing the river along Hollister Street. At night,

the sounds of flowing water, frog calls and buzzing insects fill the air;

owls fly silently overhead.

Not so obvious is the way in which flooding and contamination

have weakened the wetlands throughout the valley. Wetlands have always had

to adapt to seasonal fluctuations, but these more recent additions of pollution,

increased freshwater runoff, and development along their margins has made

them more vulnerable to rapidly changing conditions. The wetlands may now

require human interventions - specifically, the completion of a flood control

project, and the construction of an international wastewater treatment plant

- in order to survive.

Not so obvious is the way in which flooding and contamination

have weakened the wetlands throughout the valley. Wetlands have always had

to adapt to seasonal fluctuations, but these more recent additions of pollution,

increased freshwater runoff, and development along their margins has made

them more vulnerable to rapidly changing conditions. The wetlands may now

require human interventions - specifically, the completion of a flood control

project, and the construction of an international wastewater treatment plant

- in order to survive.

Predictably, some believe these plans will be the valley's

salvation, while others worry that shortsighted, poorly-designed solutions

could lead to even worse ecological conditions. Consequently, both the flood

control and sewage treatment plans have been proceeding slowly, working

their way through various stages of the public review, environmental assessment

and design process.

Predictably, some believe these plans will be the valley's

salvation, while others worry that shortsighted, poorly-designed solutions

could lead to even worse ecological conditions. Consequently, both the flood

control and sewage treatment plans have been proceeding slowly, working

their way through various stages of the public review, environmental assessment

and design process.

Collectively, these projects will cost taxpayers hundreds

of millions of dollars and take several years to construct. But for the

people who live, work and recreate in the valley, they appear to be the

answer to decades of problems.

Collectively, these projects will cost taxpayers hundreds

of millions of dollars and take several years to construct. But for the

people who live, work and recreate in the valley, they appear to be the

answer to decades of problems.

Flood control task force

Planning for San Diego's latest flood control project

began in 1993, after heavy rains and flooding caused an estimated $25 million

in damages throughout the valley. Mayor Susan Golding, County Supervisor

Brian Bilbray, and U.S. Congressman Bob Filner convened the Tijuana River

Valley Task Force.

Planning for San Diego's latest flood control project

began in 1993, after heavy rains and flooding caused an estimated $25 million

in damages throughout the valley. Mayor Susan Golding, County Supervisor

Brian Bilbray, and U.S. Congressman Bob Filner convened the Tijuana River

Valley Task Force.

Members included representatives from public resource

agencies such as California Fish and Game and U.S. Fish and Wildlife; city,

county and state elected officials; the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,

and conservation and environmental organizations such as the National Audubon

Society.

Members included representatives from public resource

agencies such as California Fish and Game and U.S. Fish and Wildlife; city,

county and state elected officials; the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,

and conservation and environmental organizations such as the National Audubon

Society.

City engineer Frank Belock was appointed chairman of

the Task Force. Belock currently is the city's Assistant Director of Engineering

Design. His job has three components. First, he was to evaluate what had

gone wrong with existing flood control measures. Second, he was charged

with making improvements and repairs to restore basic services in the valley

as quickly as possible. This would allow residents to return to their homes

and businesses. Third, he was to come up with a long-term plan to prevent

future disasters.

City engineer Frank Belock was appointed chairman of

the Task Force. Belock currently is the city's Assistant Director of Engineering

Design. His job has three components. First, he was to evaluate what had

gone wrong with existing flood control measures. Second, he was charged

with making improvements and repairs to restore basic services in the valley

as quickly as possible. This would allow residents to return to their homes

and businesses. Third, he was to come up with a long-term plan to prevent

future disasters.

"Initially there was a lot of yelling and crying

and things like that," Belock recalled in a recent interview, "but

meetings settled down once the rains stopped.

"Initially there was a lot of yelling and crying

and things like that," Belock recalled in a recent interview, "but

meetings settled down once the rains stopped.

"I think now that the City and the Task Force has

gotten a lot of things done down there, they see that something is happening."

The meetings are now much calmer, more cooperative affairs.

"I think now that the City and the Task Force has

gotten a lot of things done down there, they see that something is happening."

The meetings are now much calmer, more cooperative affairs.

During the winter of 1993 the city organized and conducted

immediate clean-up efforts, and later that year hired BSI Consultants, an

environmental design firm, to come up with several possible long-term flood

control plans. In January 1994, after months of analysis and study, BSI

Consultants presented the Task Force with ten sets of plans, ranging in

cost from $0 (the "Do nothing at all" alternative) to $160 million

(the "100 year earthen channel" alternative - meaning it could

control a huge flood that might occur every 100 years). Three of these plans

are now under final evaluation.

During the winter of 1993 the city organized and conducted

immediate clean-up efforts, and later that year hired BSI Consultants, an

environmental design firm, to come up with several possible long-term flood

control plans. In January 1994, after months of analysis and study, BSI

Consultants presented the Task Force with ten sets of plans, ranging in

cost from $0 (the "Do nothing at all" alternative) to $160 million

(the "100 year earthen channel" alternative - meaning it could

control a huge flood that might occur every 100 years). Three of these plans

are now under final evaluation.

Another alternative, designed by WEST Consultants of

Carlsbad at the request of the Tia Juana Valley County Water District, has

also been accepted for further review. This project has an estimated cost

of $31 million and would construct an earthen channel sufficient to control

a 25-year flood.

Another alternative, designed by WEST Consultants of

Carlsbad at the request of the Tia Juana Valley County Water District, has

also been accepted for further review. This project has an estimated cost

of $31 million and would construct an earthen channel sufficient to control

a 25-year flood.

The debate

Whatever plan is selected, disagreements over which

activities will be allowed to continue in the valley and which will need

to be phased out remain to be settled.

Whatever plan is selected, disagreements over which

activities will be allowed to continue in the valley and which will need

to be phased out remain to be settled.

Task Force member Jim Peugh is on one side of the debate.

Peugh is President of the local chapter of the Audubon Society and represents

the city of San Diego's Wetlands Advisory Board. He thinks it is possible

to maintain some of the existing agricultural and recreational businesses

in the valley, such as sod farms and riding stables, but doesn't believe

a massive flood channel should be seen as the final solution to protecting

larger business investments.

Task Force member Jim Peugh is on one side of the debate.

Peugh is President of the local chapter of the Audubon Society and represents

the city of San Diego's Wetlands Advisory Board. He thinks it is possible

to maintain some of the existing agricultural and recreational businesses

in the valley, such as sod farms and riding stables, but doesn't believe

a massive flood channel should be seen as the final solution to protecting

larger business investments.

"We need to use [the valley] understanding floods

are likely and realizing no matter how much infrastructure we put in down

there, floods are still a frequent and serious risk," he said recently.

"If a person is going to put enough of an investment in that they feel

uncomfortable about the occasional flood, then that particular application

isn't good for that area."

"We need to use [the valley] understanding floods

are likely and realizing no matter how much infrastructure we put in down

there, floods are still a frequent and serious risk," he said recently.

"If a person is going to put enough of an investment in that they feel

uncomfortable about the occasional flood, then that particular application

isn't good for that area."

Meanwhile, Task Force member Carolyn Powers wants to

keep the valley available for the outdoor recreational businesses and users

who have lived and played there for decades. She represents Citizens Against

Recreational Evictions (C.A.R.E) and worries that environmental considerations

may be used to force some people out of the valley.

Meanwhile, Task Force member Carolyn Powers wants to

keep the valley available for the outdoor recreational businesses and users

who have lived and played there for decades. She represents Citizens Against

Recreational Evictions (C.A.R.E) and worries that environmental considerations

may be used to force some people out of the valley.

Powers believes many recreational activities, such as

horseback riding and mountain biking, are completely compatible with the

river and its endangered species. As an example, she claims that "The

least Bell's vireo grew up around the horse trails as their habitat grew

up around the horse trails" over the last twenty to thirty years, when

many agricultural businesses ceased operations and native riparian vegetation

moved back into vacant fields.

Powers believes many recreational activities, such as

horseback riding and mountain biking, are completely compatible with the

river and its endangered species. As an example, she claims that "The

least Bell's vireo grew up around the horse trails as their habitat grew

up around the horse trails" over the last twenty to thirty years, when

many agricultural businesses ceased operations and native riparian vegetation

moved back into vacant fields.

The final decision regarding which alternative will

be selected, and what parts of the valley will be impacted, will be made

later this year by the San Diego City Council. Belock estimates it will

be another one and one-half to two years before construction begins, following

approval of the project by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Army Corps of

Engineers, and other natural resource agencies.

The final decision regarding which alternative will

be selected, and what parts of the valley will be impacted, will be made

later this year by the San Diego City Council. Belock estimates it will

be another one and one-half to two years before construction begins, following

approval of the project by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Army Corps of

Engineers, and other natural resource agencies.

River of chemicals

Each night, as the cat-and-mouse game of illegal immigration

plays itself out along the hillsides, wastewater flows into the valley from

Tijuana's overburdened sewage system, rushing through the narrow canyons

and eventually flowing into the river and estuary. At Goat Canyon, the water

runs through a shallow concrete channel over Monument Road. It has a strong

odor, redolent of human waste and chemicals.

Each night, as the cat-and-mouse game of illegal immigration

plays itself out along the hillsides, wastewater flows into the valley from

Tijuana's overburdened sewage system, rushing through the narrow canyons

and eventually flowing into the river and estuary. At Goat Canyon, the water

runs through a shallow concrete channel over Monument Road. It has a strong

odor, redolent of human waste and chemicals.

Wetlands researchers and water district employees call

these "renegade flows." In addition to carrying household wastes,

they are filled with industrial contaminants such as PCB's, and agricultural

chemicals, including DDT. Small rocks, dislodged by the water, tumble down

the hillside and litter the roadway.

Wetlands researchers and water district employees call

these "renegade flows." In addition to carrying household wastes,

they are filled with industrial contaminants such as PCB's, and agricultural

chemicals, including DDT. Small rocks, dislodged by the water, tumble down

the hillside and litter the roadway.

As the population of Tijuana has increased over the

last 10 years, the city has improved its water delivery services to homes,

but its sewage treatment system has not been able to handle the increased

demands. The result is that more and more of this wastewater has poured

into the Tijuana River and its estuary, polluting the waters, diluting the

saltwater, and disturbing the balance of the salt marsh.

As the population of Tijuana has increased over the

last 10 years, the city has improved its water delivery services to homes,

but its sewage treatment system has not been able to handle the increased

demands. The result is that more and more of this wastewater has poured

into the Tijuana River and its estuary, polluting the waters, diluting the

saltwater, and disturbing the balance of the salt marsh.

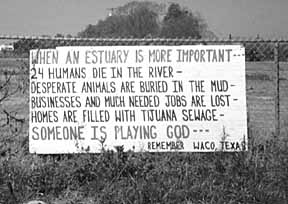

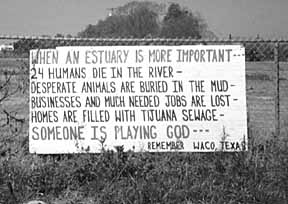

As delays over flood control and sewage clean up continue,

the anger and frustration of at least one property owner has been expressed

publicly on several crude plywood signs. They were erected in the spring

of 1993, but still stand, their words painted in capital letters with red

and black paint.

As delays over flood control and sewage clean up continue,

the anger and frustration of at least one property owner has been expressed

publicly on several crude plywood signs. They were erected in the spring

of 1993, but still stand, their words painted in capital letters with red

and black paint.

The signs carry messages such as "WELCOME TO THE

TIJUANA RIVER VALLEY WHERE BIRDS FLY AND PEOPLE DIE." One horse corral

fence supports a sign reading "ENVIRONMENTALISTS DESTROY HUMAN LIVES

AND RUIN BUSINESSES."

The signs carry messages such as "WELCOME TO THE

TIJUANA RIVER VALLEY WHERE BIRDS FLY AND PEOPLE DIE." One horse corral

fence supports a sign reading "ENVIRONMENTALISTS DESTROY HUMAN LIVES

AND RUIN BUSINESSES."

EPA plant approval

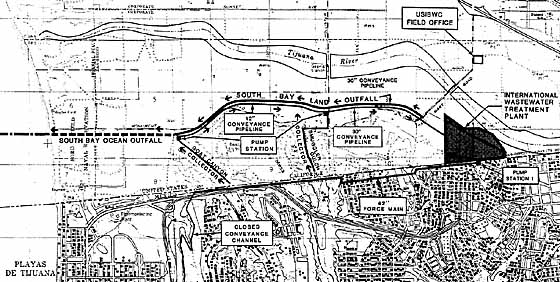

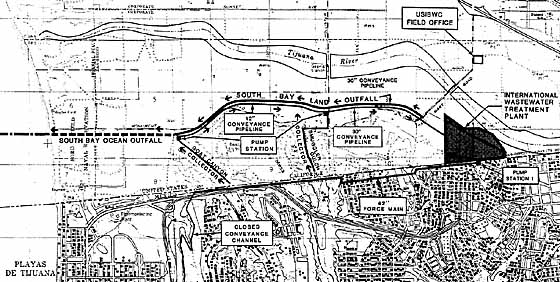

On April 1, final comments on a massive International

Wastewater Treatment Plant and Ocean Outfall plan were due in the Los Angeles

office of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Despite questions

about this plant's ability to remove toxics, the lack of an ocean outfall

for the first three years of operation, and its enormous construction, operation

and maintenance costs, the plan was approved on May 6.

On April 1, final comments on a massive International

Wastewater Treatment Plant and Ocean Outfall plan were due in the Los Angeles

office of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Despite questions

about this plant's ability to remove toxics, the lack of an ocean outfall

for the first three years of operation, and its enormous construction, operation

and maintenance costs, the plan was approved on May 6.

According to the project's Final Environmental Impact

Statement (FEIS), the proposed plant and outfall will take three years to

construct and cost $266 million, with expected annual operational and maintenance

costs between $8 and $10 million. Congress has allocated only $239 million

for the project, but it is expected that the city of San Diego will contribute

funds for the outfall (which they retain rights to use) and the government

of Mexico will contribute $16 million originally budgeted for a treatment

plant in Tijuana. The state of California will contribute $10 million.

According to the project's Final Environmental Impact

Statement (FEIS), the proposed plant and outfall will take three years to

construct and cost $266 million, with expected annual operational and maintenance

costs between $8 and $10 million. Congress has allocated only $239 million

for the project, but it is expected that the city of San Diego will contribute

funds for the outfall (which they retain rights to use) and the government

of Mexico will contribute $16 million originally budgeted for a treatment

plant in Tijuana. The state of California will contribute $10 million.

The plant - scheduled to begin operations in 1995 -

will collect wastewater overflows from Mexico, and initially treat 25 million

gallons of sewage per day, reaching advanced primary treatment levels by

using "activated sludge" and mechanical treatment methods. By

1998, it will treat wastes to secondary levels as required by the Clean

Water Act before releasing the effluent (treated wastewater) back into the

Pacific Ocean via an ocean outfall pipe tunneled under the estuary. The

remaining solids, called "sludge," will be loaded into trucks

and returned to Mexico for disposal.

The plant - scheduled to begin operations in 1995 -

will collect wastewater overflows from Mexico, and initially treat 25 million

gallons of sewage per day, reaching advanced primary treatment levels by

using "activated sludge" and mechanical treatment methods. By

1998, it will treat wastes to secondary levels as required by the Clean

Water Act before releasing the effluent (treated wastewater) back into the

Pacific Ocean via an ocean outfall pipe tunneled under the estuary. The

remaining solids, called "sludge," will be loaded into trucks

and returned to Mexico for disposal.

The ocean outfall has been designed to carry 258 million

gallons of effluent out to sea each day, with the city of San Diego eventually

using the bulk of this capacity. The "lead agencies," sharing

responsibility for the project, are the United States Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA) and the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC).

The ocean outfall has been designed to carry 258 million

gallons of effluent out to sea each day, with the city of San Diego eventually

using the bulk of this capacity. The "lead agencies," sharing

responsibility for the project, are the United States Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA) and the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC).

While the plant is a definite improvement over the existing

conditions, questions have been raised regarding its effectiveness in detoxifying

the wastewater it collects. Numerous highly toxic chemicals have been identified

in this runoff. If these chemicals collect in the sludge, they could create

a toxic waste handling and disposal problem. If they are allowed to pass

through the ocean outfall without more dilution than is currently called

for in the proposed plan, they will continue to contaminate the waters off

the coast.

While the plant is a definite improvement over the existing

conditions, questions have been raised regarding its effectiveness in detoxifying

the wastewater it collects. Numerous highly toxic chemicals have been identified

in this runoff. If these chemicals collect in the sludge, they could create

a toxic waste handling and disposal problem. If they are allowed to pass

through the ocean outfall without more dilution than is currently called

for in the proposed plan, they will continue to contaminate the waters off

the coast.

Returning waste

Technically, some of these industrial wastes should

be disposed of in their country of origin, and that may in fact be the United

States. Under the La Paz Treaty of 1983, signed by President Reagan and

Mexican President de la Madrid, hazardous wastes produced by an industry

operating in one country must be returned for disposal to the country that

owns that business, or disposed of in an approved hazardous waste site in

Mexico. Thus, the treaty requires that American-owned industries operating

in Mexico (commonly known as "maquiladoras") manage their toxic

waste in an environmentally safe way.

Technically, some of these industrial wastes should

be disposed of in their country of origin, and that may in fact be the United

States. Under the La Paz Treaty of 1983, signed by President Reagan and

Mexican President de la Madrid, hazardous wastes produced by an industry

operating in one country must be returned for disposal to the country that

owns that business, or disposed of in an approved hazardous waste site in

Mexico. Thus, the treaty requires that American-owned industries operating

in Mexico (commonly known as "maquiladoras") manage their toxic

waste in an environmentally safe way.

However, because of lax enforcement, operators often

dispose of these wastes illegally in landfills in Mexico. This is the belief

of Martha Rocha Rodriquez. She lives in the Playas neighborhood of Tijuana

and for the last five years has worked with an environmental organization

known as MEBAC, the "Movimiento Ecologista de Baja California."

However, because of lax enforcement, operators often

dispose of these wastes illegally in landfills in Mexico. This is the belief

of Martha Rocha Rodriquez. She lives in the Playas neighborhood of Tijuana

and for the last five years has worked with an environmental organization

known as MEBAC, the "Movimiento Ecologista de Baja California."

Last year, MEBAC forced a company to dismantle and remove

a proposed waste incinerator plant scheduled to operate just south of Tijuana,

arguing that it would create a health risk for nearby neighborhoods. However,

another division of the plant - owned by Chemical Waste Management de Mexico,

and located less than a mile from the Pacific Ocean - continues to recycle

solvents from maquiladoras.

Last year, MEBAC forced a company to dismantle and remove

a proposed waste incinerator plant scheduled to operate just south of Tijuana,

arguing that it would create a health risk for nearby neighborhoods. However,

another division of the plant - owned by Chemical Waste Management de Mexico,

and located less than a mile from the Pacific Ocean - continues to recycle

solvents from maquiladoras.

Rodriguez believes it is possible to reduce the amount

of wastes now being produced by American-owned maquiladoras in Tijuana,

but that high program costs and a lack of enforcement of existing laws by

SEDESOL (Mexico's Secretariat of Social Development, similar to the United

State's EPA) have made this unlikely.

Rodriguez believes it is possible to reduce the amount

of wastes now being produced by American-owned maquiladoras in Tijuana,

but that high program costs and a lack of enforcement of existing laws by

SEDESOL (Mexico's Secretariat of Social Development, similar to the United

State's EPA) have made this unlikely.

Still, the Final Environmental Impact Statement for

the new wastewater treatment plant describes a plan that will reduce these

toxic wastes through pretreatment and source reduction programs in Mexico.

It's not explained who will fund and enforce these pretreatment programs

or when they will be enacted.

Still, the Final Environmental Impact Statement for

the new wastewater treatment plant describes a plan that will reduce these

toxic wastes through pretreatment and source reduction programs in Mexico.

It's not explained who will fund and enforce these pretreatment programs

or when they will be enacted.

Art Letter, General Manager of the Tia Juana Valley

County Water District, says his organization "would encourage the International

Boundary and Water Commission to work with Mexico to treat the water to

the highest possible standards we can get."

Art Letter, General Manager of the Tia Juana Valley

County Water District, says his organization "would encourage the International

Boundary and Water Commission to work with Mexico to treat the water to

the highest possible standards we can get."

Yet another question about this plant involves the time-line

for completion of the ocean outfall. The plant is scheduled to begin operating

at advanced primary treatment levels as early as 1995, but the ocean outfall

will not be completed until 1998. The FEIS does not explain what will happen

to the millions of gallons of effluent produced during those three years.

Yet another question about this plant involves the time-line

for completion of the ocean outfall. The plant is scheduled to begin operating

at advanced primary treatment levels as early as 1995, but the ocean outfall

will not be completed until 1998. The FEIS does not explain what will happen

to the millions of gallons of effluent produced during those three years.

Art Letter discussed the possibility of injecting the

effluent back into the valley to recharge the groundwater supplies. He claimed,

"that's better water, even at Advanced Primary standards, then the

water running off from Mexico right now, which of course is totally untreated."

But when it was pointed out that the toxics might contaminate this water,

used by residents for drinking and irrigation, he conceded more study was

needed.

Art Letter discussed the possibility of injecting the

effluent back into the valley to recharge the groundwater supplies. He claimed,

"that's better water, even at Advanced Primary standards, then the

water running off from Mexico right now, which of course is totally untreated."

But when it was pointed out that the toxics might contaminate this water,

used by residents for drinking and irrigation, he conceded more study was

needed.

Dave Schlesinger is the Director of the Metropolitan

Wastewater District for the City of San Diego. He reviewed the treatment

plant's Final Environmental Impact Statement and submitted comments for

the city. He also doesn't know exactly what will be done with the effluent

before the outfall is constructed, but he suggested a few alternatives.

Dave Schlesinger is the Director of the Metropolitan

Wastewater District for the City of San Diego. He reviewed the treatment

plant's Final Environmental Impact Statement and submitted comments for

the city. He also doesn't know exactly what will be done with the effluent

before the outfall is constructed, but he suggested a few alternatives.

"There are ways you can do it. You can have live-stream

discharge, you can have a groundwater application, you can try to send it

back to Mexico. But ... that's not addressed in that environmental document

[the Final Environmental Impact Statement], and that's one of the city's

major concerns."

"There are ways you can do it. You can have live-stream

discharge, you can have a groundwater application, you can try to send it

back to Mexico. But ... that's not addressed in that environmental document

[the Final Environmental Impact Statement], and that's one of the city's

major concerns."

Schlesinger also noted this factor has raised questions

- and a possible legal challenge - from the San Diego chapter of the Sierra

Club. He noted that "The Sierra Club is threatening to sue over that

document. I understand that the [federal agencies] now say they may issue

a supplemental environmental document to address the discharge issue."

Schlesinger also noted this factor has raised questions

- and a possible legal challenge - from the San Diego chapter of the Sierra

Club. He noted that "The Sierra Club is threatening to sue over that

document. I understand that the [federal agencies] now say they may issue

a supplemental environmental document to address the discharge issue."

When asked if this supplemental document will also address

the removal of toxics, he replied, "We sure hope so."

When asked if this supplemental document will also address

the removal of toxics, he replied, "We sure hope so."

A golden pond?

In April, after the public comment period for the plant's

FEIS had closed, the EPA convened a panel of sanitary engineers to evaluate

another sewage treatment design, called "Advanced Integrated Ponding

Systems," (AIPS) and consider its feasibility for use at the border

treatment plant. AIPS treats sewage via a series of interconnected ponds,

using a combination of bacterial, algae and anaerobic decomposition systems

to remove biological and industrial wastes. Toxics are absorbed by algae

or settle into the sediments on the bottom of the ponds.

In April, after the public comment period for the plant's

FEIS had closed, the EPA convened a panel of sanitary engineers to evaluate

another sewage treatment design, called "Advanced Integrated Ponding

Systems," (AIPS) and consider its feasibility for use at the border

treatment plant. AIPS treats sewage via a series of interconnected ponds,

using a combination of bacterial, algae and anaerobic decomposition systems

to remove biological and industrial wastes. Toxics are absorbed by algae

or settle into the sediments on the bottom of the ponds.

One advantage to this system is that it is more efficient

at digesting wastewater solids and can operate for years without producing

large quantities of sludge. In contrast, mechanical plants require daily

disposal of tons of sludge, which are then dried and, in the case of Tijuana,

dumped in landfills.

One advantage to this system is that it is more efficient

at digesting wastewater solids and can operate for years without producing

large quantities of sludge. In contrast, mechanical plants require daily

disposal of tons of sludge, which are then dried and, in the case of Tijuana,

dumped in landfills.

An April 25 report on this system, sent to the City

of San Diego, noted that "The major advantages of the AIPS system are

its very low initial and operating cost, simple system operation, and presumed

good stability against anticipated toxic loads. Disadvantages of the system

included limited data availability on the existing plants, variable effluent

quality, and the high land area required for the facilities."

An April 25 report on this system, sent to the City

of San Diego, noted that "The major advantages of the AIPS system are

its very low initial and operating cost, simple system operation, and presumed

good stability against anticipated toxic loads. Disadvantages of the system

included limited data availability on the existing plants, variable effluent

quality, and the high land area required for the facilities."

According to the Engineering Feasibility Team Study,

an AIPS plant would cost approximately $100 million less in capital construction

expenses than the proposed plant. The report also noted that "without

an effective pretreatment program in Tijuana, the activated sludge process

will be frequently upset, and permit limits [on toxic discharges] may be

exceeded with some regularity. The advanced primary plant will produce poorer

quality effluent than the ponds, and it will allow soluble toxic compounds

to be discharged directly to the ocean."

According to the Engineering Feasibility Team Study,

an AIPS plant would cost approximately $100 million less in capital construction

expenses than the proposed plant. The report also noted that "without

an effective pretreatment program in Tijuana, the activated sludge process

will be frequently upset, and permit limits [on toxic discharges] may be

exceeded with some regularity. The advanced primary plant will produce poorer

quality effluent than the ponds, and it will allow soluble toxic compounds

to be discharged directly to the ocean."

Nonetheless, on April 27, the Policy Committee for this

project rejected the ponding alternative, deciding to proceed with the plant

as originally designed. Notes from this meeting show, "It was agreed

that ponds will be dropped from further consideration for the initial phase

of the International Treatment Plant, but will be considered for any future

expansion."

Nonetheless, on April 27, the Policy Committee for this

project rejected the ponding alternative, deciding to proceed with the plant

as originally designed. Notes from this meeting show, "It was agreed

that ponds will be dropped from further consideration for the initial phase

of the International Treatment Plant, but will be considered for any future

expansion."

Critics of this decision point out that the AIPS study

cost $51,000 and took less than a week to conduct. In contrast, the EPA

and IBWC have spent millions of dollars and devoted years of study to the

design of the chosen alternative.

Critics of this decision point out that the AIPS study

cost $51,000 and took less than a week to conduct. In contrast, the EPA

and IBWC have spent millions of dollars and devoted years of study to the

design of the chosen alternative.

Examples of treatment ponds in an Advanced Integrated Ponding

System, part of the St. Helena Wastewater Treatment Plant in Napa Valley,

CA. Wastewater progressing through five ponds is progressively broken down

before release. Proponents quote cost savings as well as environmental benefits

over traditional mechanical plants.

More talk

The complicated nature of cleaning up this valley continues

to frustrate residents, land use managers, and city, state and federal officials.

While these two latest plans appear promising, they are several years away

from providing solutions for the flooding and sewage problems that threaten

the valley each winter. And the Sierra Club is still considering filing

a legal challenge to the wastewater plant, arguing, among other things,

that the ponding system alternative was not given a full evaluation.

The complicated nature of cleaning up this valley continues

to frustrate residents, land use managers, and city, state and federal officials.

While these two latest plans appear promising, they are several years away

from providing solutions for the flooding and sewage problems that threaten

the valley each winter. And the Sierra Club is still considering filing

a legal challenge to the wastewater plant, arguing, among other things,

that the ponding system alternative was not given a full evaluation.

Still, Frank Belock remains optimistic. He has worked

on this project for over a year and appreciates the challenge of creating

a solution that works for everyone. At the end of our interview he concluded

that, "Our purpose is to provide an alternative that hopefully balances

the needs of the people that live in the valley, with the various habitats

that exist there, such as the riparian, wetlands, least Bell's vireo, and

the habitat in the estuary itself. That's part of what we're working with

- trying to balance all this."

Still, Frank Belock remains optimistic. He has worked

on this project for over a year and appreciates the challenge of creating

a solution that works for everyone. At the end of our interview he concluded

that, "Our purpose is to provide an alternative that hopefully balances

the needs of the people that live in the valley, with the various habitats

that exist there, such as the riparian, wetlands, least Bell's vireo, and

the habitat in the estuary itself. That's part of what we're working with

- trying to balance all this."

Lori Saldaña. a regular contributor to Earth Times, is a writer,

public speaker and photographer who specializes in conservation and environmental

issues.