Saving the endangered sea turtle

Who says you can't make a difference? Two Mexican biologists and

two American ecologists/entrepreneurs have taken a stand for sea turtle

populations that is having a profound effect. And, they're inviting you

to join them.

by Alice Martinez

hroughout the world, there are a number of serious,

ongoing projects to restore and preserve sea turtles and their habitats.

What follows is the story of one such effort, located in nearby Baja California,

Mexico.

hroughout the world, there are a number of serious,

ongoing projects to restore and preserve sea turtles and their habitats.

What follows is the story of one such effort, located in nearby Baja California,

Mexico.

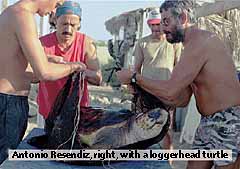

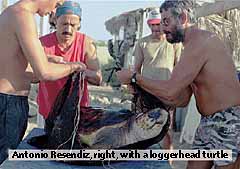

In 1978, at the age of 24, Antonio Resendiz moved to

Bahia de Los Angeles to manage a sea turtle conservation project funded

by the Mexican Instituto de Pesca (Fish Institute). Bahia de Los Angeles

is a remote fishing pueblo located on the Sea of Cortez about 400 miles

south of San Diego. This region of bays and islands is host to one of the

world's richest aquatic communities. Visitors are often surprised while

snorkeling by curious sea lions, by orca feeding close by or by having their

boats escorted by playful dolphins.

In 1978, at the age of 24, Antonio Resendiz moved to

Bahia de Los Angeles to manage a sea turtle conservation project funded

by the Mexican Instituto de Pesca (Fish Institute). Bahia de Los Angeles

is a remote fishing pueblo located on the Sea of Cortez about 400 miles

south of San Diego. This region of bays and islands is host to one of the

world's richest aquatic communities. Visitors are often surprised while

snorkeling by curious sea lions, by orca feeding close by or by having their

boats escorted by playful dolphins.

At Bahia de Los Angeles, Antonio lived and worked alone

in a pueblo of traditional fishermen and turtlers. He fought to educate

the local people about marine biology and the need to conserve the area's

aquatic life. His confiscation of illegally captured turtles and turtle

nets and his documentation of other illegal fishing practices sometimes

brought him into dangerous confrontations.

At Bahia de Los Angeles, Antonio lived and worked alone

in a pueblo of traditional fishermen and turtlers. He fought to educate

the local people about marine biology and the need to conserve the area's

aquatic life. His confiscation of illegally captured turtles and turtle

nets and his documentation of other illegal fishing practices sometimes

brought him into dangerous confrontations.

In 1988, Antonio took on a research partner (and subsequent

marriage partner) Beatrice (Bety) Jimenez. Bety received her biology degrees

from the University of Michoacan. Prior to meeting Antonio, she had spent

ten years at a leatherback sea turtle nursery in Michoacan. Her work there

consisted in part of long nights walking the beaches to safeguard nesting

turtles and their eggs from poachers.

In 1988, Antonio took on a research partner (and subsequent

marriage partner) Beatrice (Bety) Jimenez. Bety received her biology degrees

from the University of Michoacan. Prior to meeting Antonio, she had spent

ten years at a leatherback sea turtle nursery in Michoacan. Her work there

consisted in part of long nights walking the beaches to safeguard nesting

turtles and their eggs from poachers.

The couple's overall aim is to protect the region's

fisheries and stocks of marine mammals and sea birds, as well as sea turtles.

Information gathered by the Resendiz family is being used to help guide

sea turtle conservation around the world.

The couple's overall aim is to protect the region's

fisheries and stocks of marine mammals and sea birds, as well as sea turtles.

Information gathered by the Resendiz family is being used to help guide

sea turtle conservation around the world.

Adjacent to the center, the family has developed a small

campground, Campo Archelon, proceeds from which help support their work.

It is here that they host visiting scientists.

Adjacent to the center, the family has developed a small

campground, Campo Archelon, proceeds from which help support their work.

It is here that they host visiting scientists.

Mexican reserves

Four of Mexico's 17 beach reserves are located in the

state of Jalisco and managed by the University of Guadalajara in conjunction

with the government and private organizations. Since 1982, the university

has been developing a program to conserve Jalisco's sea turtle population

through protection, research and education. Beach reserves are protected

from poachers to the extent that money will allow. Biologists and students

live and work at camps on remote beaches trying to revive the sea turtle

population. A research program was started in 1987 to study the life patterns

of hatchlings in their first year.

Four of Mexico's 17 beach reserves are located in the

state of Jalisco and managed by the University of Guadalajara in conjunction

with the government and private organizations. Since 1982, the university

has been developing a program to conserve Jalisco's sea turtle population

through protection, research and education. Beach reserves are protected

from poachers to the extent that money will allow. Biologists and students

live and work at camps on remote beaches trying to revive the sea turtle

population. A research program was started in 1987 to study the life patterns

of hatchlings in their first year.

The government sea turtle station currently supports

a small population of juvenile and adult turtles for research and education.

Holding tanks have been built to hold three species of sea turtle: loggerhead

(Caretta caretta), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata squamata),

and pacific black (Chelo-nia mydas agassizii).

The government sea turtle station currently supports

a small population of juvenile and adult turtles for research and education.

Holding tanks have been built to hold three species of sea turtle: loggerhead

(Caretta caretta), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata squamata),

and pacific black (Chelo-nia mydas agassizii).

One man steps forward

In the summer of 1991, Carl Worl planned a three-week

trip to Baja after graduating from Colorado State University. Carl was interested

in experiencing the natural wonders of Baja and wanted to volunteer some

of his time for wild life preservation or a research project.

In the summer of 1991, Carl Worl planned a three-week

trip to Baja after graduating from Colorado State University. Carl was interested

in experiencing the natural wonders of Baja and wanted to volunteer some

of his time for wild life preservation or a research project.

During his travels, he met Antonio - who needed lots

of help. Antonio's preservation work and research immediately struck a responsive

cord with Carl. Carl started helping with various tasks around the camp:

building palapas, painting, running errands - all those mundane tasks that

are essential to supporting a field station.

During his travels, he met Antonio - who needed lots

of help. Antonio's preservation work and research immediately struck a responsive

cord with Carl. Carl started helping with various tasks around the camp:

building palapas, painting, running errands - all those mundane tasks that

are essential to supporting a field station.

He was also captivated by Antonio's spirit. "Antonio

has so much enthusiasm. He never stops," explains Carl. "He runs

everywhere - he doesn't walk. He talks so fast and his voice projects so

much ... it lights people up."

He was also captivated by Antonio's spirit. "Antonio

has so much enthusiasm. He never stops," explains Carl. "He runs

everywhere - he doesn't walk. He talks so fast and his voice projects so

much ... it lights people up."

Carl's three-week trip turned into 5 months.

Carl's three-week trip turned into 5 months.

In 1992, Carl met Heather Paige, a graphic artist vacationing

in Baja. Heather was discouraged by the people's attitude toward the environment.

"Society is so wasteful, it has to stop at some point," she says.

In 1992, Carl met Heather Paige, a graphic artist vacationing

in Baja. Heather was discouraged by the people's attitude toward the environment.

"Society is so wasteful, it has to stop at some point," she says.

Working with Antonio and Carl proved to be the anodyne

to her disillusionment. Together, Heather and Carl decided to work together

to further turtle preservation.

Working with Antonio and Carl proved to be the anodyne

to her disillusionment. Together, Heather and Carl decided to work together

to further turtle preservation.

Later that year they went on a four-month pilgrimage

to Michoacan to do volunteer work, ranging as far south as Guerrero. Visiting

beach after beach, their level of concern escalated.

Later that year they went on a four-month pilgrimage

to Michoacan to do volunteer work, ranging as far south as Guerrero. Visiting

beach after beach, their level of concern escalated.

"We went to a lot of deserted beaches that didn't

have projects," says Carl. "There were a lot of turtles coming

up and they were all poached. On some beaches, we could count, say, 40 nests

that were all poached - every single one of them."

"We went to a lot of deserted beaches that didn't

have projects," says Carl. "There were a lot of turtles coming

up and they were all poached. On some beaches, we could count, say, 40 nests

that were all poached - every single one of them."

This direct experience of habitat devastation had a

profound effect on Carl and Heather. "The sea turtles seem to be almost

spiritual creatures - great turtle spirits," explains Heather. To allow

the destruction to continue was unacceptable.

This direct experience of habitat devastation had a

profound effect on Carl and Heather. "The sea turtles seem to be almost

spiritual creatures - great turtle spirits," explains Heather. To allow

the destruction to continue was unacceptable.

Carl and Heather are unable to say exactly when or how

they decided to commit themselves to sea turtle preservation; however, the

future direction of their lives had been decided.

Carl and Heather are unable to say exactly when or how

they decided to commit themselves to sea turtle preservation; however, the

future direction of their lives had been decided.

Spreading the word

Having experienced the personal transformation resulting

from direct exposure to the destruction of species and natural habitats,

they committed themselves to finding a way to share the experience.

Having experienced the personal transformation resulting

from direct exposure to the destruction of species and natural habitats,

they committed themselves to finding a way to share the experience.

"The biggest problem with environmentalism is pushing

all this literature," says Carl. "I'm not putting it down, because

there's no other alternative. But it doesn't carry the feeling. When Greenpeace

sends the literature about the dolphins, it's so detached .... But if the

people got out and actually went on their boat and saw the animals, then

they might really change their attitudes. I've seen people actually change

when they go and deal with the animals - do the work to help them. But when

they just see it on TV, it's just another thing."

"The biggest problem with environmentalism is pushing

all this literature," says Carl. "I'm not putting it down, because

there's no other alternative. But it doesn't carry the feeling. When Greenpeace

sends the literature about the dolphins, it's so detached .... But if the

people got out and actually went on their boat and saw the animals, then

they might really change their attitudes. I've seen people actually change

when they go and deal with the animals - do the work to help them. But when

they just see it on TV, it's just another thing."

Contacting a number of well-known environmental groups,

they discovered that most were charging "volunteers" $900 a week

and up! Many individuals were more than willing to donate labor and some

money, but these rates were simply beyond most budgets.

Contacting a number of well-known environmental groups,

they discovered that most were charging "volunteers" $900 a week

and up! Many individuals were more than willing to donate labor and some

money, but these rates were simply beyond most budgets.

After a little more digging, they discovered that there

were many biologists and small conservation projects that needed their kind

of support. They soon recognized the need for a low-cost alternative - a

way to pair willing (but not rich) volunteers like themselves with scientists

doing critical, but often underfunded, field research. They realized that

the scientists' efforts alone are inadequate - there simply aren't enough

of them. Moreover, achieving their goals will take the whole community working

together.

After a little more digging, they discovered that there

were many biologists and small conservation projects that needed their kind

of support. They soon recognized the need for a low-cost alternative - a

way to pair willing (but not rich) volunteers like themselves with scientists

doing critical, but often underfunded, field research. They realized that

the scientists' efforts alone are inadequate - there simply aren't enough

of them. Moreover, achieving their goals will take the whole community working

together.

In 1993, Carl and Heather formed One World Work Force

(OWWF), a nonprofit organization, expressly to address this need. The goal

of OWWF is to provide others with the opportunity to lend a hand with conservation

research, species protection and other efforts to save our planet. By maintaining

a low overhead and using donated equipment, they offer the chance to spend

a week working with a scientist in the field at half the cost of other organizations.

Their small staff is supplemented by volunteer assistance.

In 1993, Carl and Heather formed One World Work Force

(OWWF), a nonprofit organization, expressly to address this need. The goal

of OWWF is to provide others with the opportunity to lend a hand with conservation

research, species protection and other efforts to save our planet. By maintaining

a low overhead and using donated equipment, they offer the chance to spend

a week working with a scientist in the field at half the cost of other organizations.

Their small staff is supplemented by volunteer assistance.

Carl is pleased with the support that OWWF is getting

from scientists and biologists. "The scientific community is taking

us as being credible, instead of just a super eco-tour company," he

states.

Carl is pleased with the support that OWWF is getting

from scientists and biologists. "The scientific community is taking

us as being credible, instead of just a super eco-tour company," he

states.

OWWF takes off

OWWF is offering three trips in 1994 focused on scientific

research, education, habitat restoration and hands-on protection of female

sea turtles and their eggs during the nesting season. The trips will be

to Antonio's center at Bahia de Los Angeles and to Tenacatita Beach and

Mismaloya Beach on the Mexican mainland.

OWWF is offering three trips in 1994 focused on scientific

research, education, habitat restoration and hands-on protection of female

sea turtles and their eggs during the nesting season. The trips will be

to Antonio's center at Bahia de Los Angeles and to Tenacatita Beach and

Mismaloya Beach on the Mexican mainland.

At Bahia de los Angeles, OWWF makes their base camp

at Campo Archelon. To those for whom "nature" means tall forests

and green valleys, the site may appear desolate. But to those familiar with

the deserts of the Southwest, it is a fragile paradise.

At Bahia de los Angeles, OWWF makes their base camp

at Campo Archelon. To those for whom "nature" means tall forests

and green valleys, the site may appear desolate. But to those familiar with

the deserts of the Southwest, it is a fragile paradise.

"The area has towering mountains, tons of endemic

wildlife and plants - like 80 species of cactus found only in that area

- pristine beaches and warm, crystal-clear water," says Carl. "The

camp is natural and beautiful. The palapas are right on the beach. There

is excellent snorkeling right off the beach. The camp is natural - not developed

at all. Cactus grows right next to the palapas. Little roads wind through

the elephant trees."

"The area has towering mountains, tons of endemic

wildlife and plants - like 80 species of cactus found only in that area

- pristine beaches and warm, crystal-clear water," says Carl. "The

camp is natural and beautiful. The palapas are right on the beach. There

is excellent snorkeling right off the beach. The camp is natural - not developed

at all. Cactus grows right next to the palapas. Little roads wind through

the elephant trees."

Each morning, the team helps clean and refill the turtle

tanks. Other daily projects include collecting food for the turtles in order

to maintain their natural diet. This entails snorkeling for seaweed and

spearfishing for fish and stingray. While maintaining the center, the Resendiz

utilize volunteers in numerous other projects, ranging from shark parasites

to sea hares (Aplysia californica).

Each morning, the team helps clean and refill the turtle

tanks. Other daily projects include collecting food for the turtles in order

to maintain their natural diet. This entails snorkeling for seaweed and

spearfishing for fish and stingray. While maintaining the center, the Resendiz

utilize volunteers in numerous other projects, ranging from shark parasites

to sea hares (Aplysia californica).

While aiding in the research conducted by Antonio and

Bety, volunteers also collect data for Scott Eckert of Hubbs-Sea World.

Efforts to protect sea turtles are handicapped by lack of knowledge of their

life cycles, migration patterns, food preferences, social structure, and

growth rates - all issues that volunteers help these researchers tackle.

Without the volunteer efforts, it would be impossible for any of this on-water

data collection and research to take place.

While aiding in the research conducted by Antonio and

Bety, volunteers also collect data for Scott Eckert of Hubbs-Sea World.

Efforts to protect sea turtles are handicapped by lack of knowledge of their

life cycles, migration patterns, food preferences, social structure, and

growth rates - all issues that volunteers help these researchers tackle.

Without the volunteer efforts, it would be impossible for any of this on-water

data collection and research to take place.

It has been said that there are no extraordinary individuals

- only ordinary individuals with an extraordinary commitment. Antonio, Bety,

Carl and Heather embody that commitment, and invite you to join them for

an extraordinary experience.

It has been said that there are no extraordinary individuals

- only ordinary individuals with an extraordinary commitment. Antonio, Bety,

Carl and Heather embody that commitment, and invite you to join them for

an extraordinary experience.

The lost arribada

Twenty years ago the Mexican state of Jalisco received

an arribada, one of nature's most awesome events. The arribada, Spanish

for "arrival", is a peculiar nesting event of the olive ridley.

In a span of only a few days, wave after wave, thousand upon thousand of

females come ashore to lay their eggs. Local fishermen who experienced it

twenty years ago claim that a person could walk down the beach on the backs

of the turtles without ever touching the sand.

Twenty years ago the Mexican state of Jalisco received

an arribada, one of nature's most awesome events. The arribada, Spanish

for "arrival", is a peculiar nesting event of the olive ridley.

In a span of only a few days, wave after wave, thousand upon thousand of

females come ashore to lay their eggs. Local fishermen who experienced it

twenty years ago claim that a person could walk down the beach on the backs

of the turtles without ever touching the sand.

At the arrival of the arribada, turtles and eggs were

harvested intensively for food and leather. The massive number of turtles

gave the false impression of an unlimited, never-ending, source of turtles.

At the arrival of the arribada, turtles and eggs were

harvested intensively for food and leather. The massive number of turtles

gave the false impression of an unlimited, never-ending, source of turtles.

The arribada no longer comes to the beaches of Jalisco.

The olive ridley population there has plummeted from approximately 20,000

- 30,000 nesting turtles in the 1960s to only about 1,000 today. Worldwide,

only 4 of the 7 beaches that used to host the arribada still experience

them.

The arribada no longer comes to the beaches of Jalisco.

The olive ridley population there has plummeted from approximately 20,000

- 30,000 nesting turtles in the 1960s to only about 1,000 today. Worldwide,

only 4 of the 7 beaches that used to host the arribada still experience

them.

Listed as an endangered species, the olive ridley now

nests intermittently in Jalisco over a broad expanse of beach, making conservation

efforts difficult and expensive.

Listed as an endangered species, the olive ridley now

nests intermittently in Jalisco over a broad expanse of beach, making conservation

efforts difficult and expensive.

A turtle nursery story

One key project is the maintenance of a sea turtle "nursery."

Sea turtle nests are carefully dug up and removed from the beach, where

they would be subject to poaching. The eggs are then reburied in the "nursery,"

a fenced-in compound where their temperature, moisture and development can

be monitored. When the eggs hatch, the young turtles are released into the

ocean.

One key project is the maintenance of a sea turtle "nursery."

Sea turtle nests are carefully dug up and removed from the beach, where

they would be subject to poaching. The eggs are then reburied in the "nursery,"

a fenced-in compound where their temperature, moisture and development can

be monitored. When the eggs hatch, the young turtles are released into the

ocean.

On one small beach, this might seem to have an insignificant

impact. The numbers tell a different story.

On one small beach, this might seem to have an insignificant

impact. The numbers tell a different story.

A sea turtle lays between 50 and 200 eggs in each nest,

which is buried in the sand. About 80 percent of these eggs may eventually

hatch and produce baby turtles. A baby turtle is very delicate. A wide variety

of natural and man-made obstacles drastically reduce their numbers.

A sea turtle lays between 50 and 200 eggs in each nest,

which is buried in the sand. About 80 percent of these eggs may eventually

hatch and produce baby turtles. A baby turtle is very delicate. A wide variety

of natural and man-made obstacles drastically reduce their numbers.

Natural beach erosion can uncover the eggs, destroying

a whole season's nesting. Animals like coyotes and racoons (and man, of

course) dig up and destroy nests.

Natural beach erosion can uncover the eggs, destroying

a whole season's nesting. Animals like coyotes and racoons (and man, of

course) dig up and destroy nests.

After emerging from the nest, the baby turtles immediately

head for the ocean. Before reaching the water they are subject to additional

problems. Crabs and birds, in addition to racoons and coyotes, find the

young turtles a tasty meal. A tire track in the sand can trap an entire

nest of young. The young are drawn to the light, so any man-made lighting

will interfere with their trek to the sea, as will sunlight if they emerge

during the day. Having to cross a road to reach the beach is obviously a

problem.

After emerging from the nest, the baby turtles immediately

head for the ocean. Before reaching the water they are subject to additional

problems. Crabs and birds, in addition to racoons and coyotes, find the

young turtles a tasty meal. A tire track in the sand can trap an entire

nest of young. The young are drawn to the light, so any man-made lighting

will interfere with their trek to the sea, as will sunlight if they emerge

during the day. Having to cross a road to reach the beach is obviously a

problem.

Once in the water, the turtles swim out to sea. They

probably swim for two days - the amount of food reserves they are born with

- without stopping. Of course, once in the water they are preyed upon by

sharks and other large fish, such as the skipjack.

Once in the water, the turtles swim out to sea. They

probably swim for two days - the amount of food reserves they are born with

- without stopping. Of course, once in the water they are preyed upon by

sharks and other large fish, such as the skipjack.

It is estimated that less than one percent of the turtles

survive to maturity.

It is estimated that less than one percent of the turtles

survive to maturity.

Eliminating land-based predators and ensuring that all

of the young turtles make it to the sea greatly increases their survival

rate. Although natural survival rates are not accurately known, one nest

that makes it to the nursery may produce the equivalent of five or 10 nests

on the beach. Survival from ten nests in the nursery may be the equivalent

of 100 "natural" nests!

Eliminating land-based predators and ensuring that all

of the young turtles make it to the sea greatly increases their survival

rate. Although natural survival rates are not accurately known, one nest

that makes it to the nursery may produce the equivalent of five or 10 nests

on the beach. Survival from ten nests in the nursery may be the equivalent

of 100 "natural" nests!

Alice Martinez is a long-term San Diego resident, environmental reporter,

computer specialist, and San Diego Earth Day volunteer.

Twenty years ago the Mexican state of Jalisco received an arribada, one of nature's most awesome events. The arribada, Spanish for "arrival", is a peculiar nesting event of the olive ridley. In a span of only a few days, wave after wave, thousand upon thousand of females come ashore to lay their eggs. Local fishermen who experienced it twenty years ago claim that a person could walk down the beach on the backs of the turtles without ever touching the sand.

At the arrival of the arribada, turtles and eggs were harvested intensively for food and leather. The massive number of turtles gave the false impression of an unlimited, never-ending, source of turtles.

The arribada no longer comes to the beaches of Jalisco. The olive ridley population there has plummeted from approximately 20,000 - 30,000 nesting turtles in the 1960s to only about 1,000 today. Worldwide, only 4 of the 7 beaches that used to host the arribada still experience them.

Listed as an endangered species, the olive ridley now nests intermittently in Jalisco over a broad expanse of beach, making conservation efforts difficult and expensive.