Saving Liberia's Rainforests

Conservation efforts are almost always after the fact: after the damage

is done, when true restoration is difficult or impossible, and one can only

preserve what little is left.

One group is working to stop damage to Liberia's rainforests before it happens!

by Karla Stang

ave the rainforest" is a now-familiar phrase. We

see it on bumper stickers, T-shirts, and posters. But where are the rainforests?

And what is actually being done to save them?

ave the rainforest" is a now-familiar phrase. We

see it on bumper stickers, T-shirts, and posters. But where are the rainforests?

And what is actually being done to save them?

Alexander L. Peal, the founder and chairman of the Society

for the Renewal of Nature Conservation in Liberia (SRNCL), offers some answers.

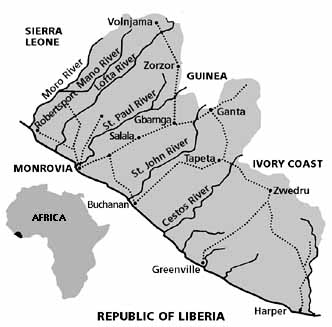

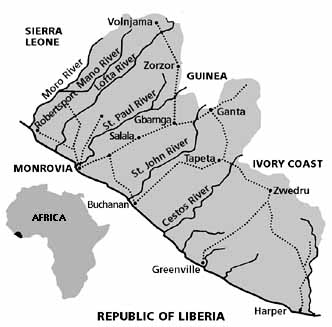

Peal is from the war-torn country of Liberia, which contains one of the

last tropical rainforests in West Africa. Considering the degree of deforestation

in neighboring countries, Liberia is a present-day refuge.

Alexander L. Peal, the founder and chairman of the Society

for the Renewal of Nature Conservation in Liberia (SRNCL), offers some answers.

Peal is from the war-torn country of Liberia, which contains one of the

last tropical rainforests in West Africa. Considering the degree of deforestation

in neighboring countries, Liberia is a present-day refuge.

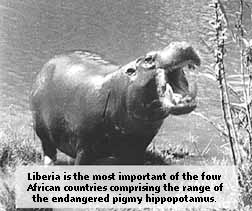

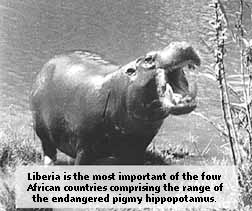

The spectacular biodiversity of Liberia is clearly worth

protecting: the forest supports 568 species of birds, 9 of which are endangered,

as well as a wide range of plant and animal life. The forest is a unique

ecological niche for several rare species, such as the white-breasted guinea

fowl, Jentink's duiker (a deer-like creature, the rarest in the world),

pygmy hippopotamus, Diana monkey and Liberian mongoose. Additional animal

populations include the giant forest hog, chimpanzees, red colobus (a long-tailed

monkey), bongo antelope, leopard and the golden cat.

The spectacular biodiversity of Liberia is clearly worth

protecting: the forest supports 568 species of birds, 9 of which are endangered,

as well as a wide range of plant and animal life. The forest is a unique

ecological niche for several rare species, such as the white-breasted guinea

fowl, Jentink's duiker (a deer-like creature, the rarest in the world),

pygmy hippopotamus, Diana monkey and Liberian mongoose. Additional animal

populations include the giant forest hog, chimpanzees, red colobus (a long-tailed

monkey), bongo antelope, leopard and the golden cat.

In the early 70s, Peal was a member of the forestry

assigned to one of the richest areas in the forest in terms of animal life.

When Peal realized that the survival of certain animals was threatened due

to hunting and deforestation, he decided to get involved in wildlife management.

He learned that there was no existing conservation program, so he created

one from scratch - the Society for Nature Conservation in Liberia (SNCL).

In the early 70s, Peal was a member of the forestry

assigned to one of the richest areas in the forest in terms of animal life.

When Peal realized that the survival of certain animals was threatened due

to hunting and deforestation, he decided to get involved in wildlife management.

He learned that there was no existing conservation program, so he created

one from scratch - the Society for Nature Conservation in Liberia (SNCL).

"We were given the challenge of educating both

the general public and government officials about the importance of nature

conservation," said Peal. Some native villagers were initially suspicious,

but when Dr. Phillip Robinson, a veterinarian for UCSD and a founding member

of the Board of Directors for SRNCL, explained that they were "wildlife

missionaries," it seemed to clear up confusion and mistrust.

"We were given the challenge of educating both

the general public and government officials about the importance of nature

conservation," said Peal. Some native villagers were initially suspicious,

but when Dr. Phillip Robinson, a veterinarian for UCSD and a founding member

of the Board of Directors for SRNCL, explained that they were "wildlife

missionaries," it seemed to clear up confusion and mistrust.

Despite the chaotic political climate of the 1980s,

nature conservation was on the upswing in Liberia. SNCL created extensive

educational programs through the schools and media to teach the general

public about protecting and conserving the environment. Other achievements

included the establishment of the first national park in Liberia, membership

in international conventions and organizations, and the development of close

bilateral working relationships with several multi-national institutions

and organizations.

Despite the chaotic political climate of the 1980s,

nature conservation was on the upswing in Liberia. SNCL created extensive

educational programs through the schools and media to teach the general

public about protecting and conserving the environment. Other achievements

included the establishment of the first national park in Liberia, membership

in international conventions and organizations, and the development of close

bilateral working relationships with several multi-national institutions

and organizations.

Fortunes of war

Civil war from 1989 through 1992 destroyed many of Liberia's

institutions, including the new conservation programs. Some of the national

park staff members were killed, and others left the area at onset of the

fighting.

Civil war from 1989 through 1992 destroyed many of Liberia's

institutions, including the new conservation programs. Some of the national

park staff members were killed, and others left the area at onset of the

fighting.

"It was difficult, because we thought we had made

so much progress, and then our dreams were literally smashed right in front

of our eyes," said Peal. "But then I remembered the importance

of what we were doing - and the lasting benefits. So I don't mind the setbacks

or the sacrifice of my time."

"It was difficult, because we thought we had made

so much progress, and then our dreams were literally smashed right in front

of our eyes," said Peal. "But then I remembered the importance

of what we were doing - and the lasting benefits. So I don't mind the setbacks

or the sacrifice of my time."

There are still ongoing skirmishes and fighting in some

areas of Liberia, and the government is very unstable. There is a peace-keeping

force and transitional government in place, and people are searching for

a peaceful solution, but efforts at conservation have not been a political

priority.

There are still ongoing skirmishes and fighting in some

areas of Liberia, and the government is very unstable. There is a peace-keeping

force and transitional government in place, and people are searching for

a peaceful solution, but efforts at conservation have not been a political

priority.

Peal relocated to the United States at the onset of

the civil war to create the "renewal" of the SNCL, in 1992. Peal,

Robinson, additional board members and volunteers have worked for the past

two years in the United States and abroad to gather support for conservation

in Liberia once the fighting stops and the new government is in place. When

peace is restored to the country, organized reconstruction of the conservation

program will need to take place at all levels - a grand effort, considering

the country's limited resources.

Peal relocated to the United States at the onset of

the civil war to create the "renewal" of the SNCL, in 1992. Peal,

Robinson, additional board members and volunteers have worked for the past

two years in the United States and abroad to gather support for conservation

in Liberia once the fighting stops and the new government is in place. When

peace is restored to the country, organized reconstruction of the conservation

program will need to take place at all levels - a grand effort, considering

the country's limited resources.

A fresh start

The new government's first priority will be to improve

the economy. SRNCL has the foresight to be organized and ready to insist

on including conservation in the overall reconstruction.

The new government's first priority will be to improve

the economy. SRNCL has the foresight to be organized and ready to insist

on including conservation in the overall reconstruction.

"We fear that too much pressure will be exerted

on the forest and other natural resources to provide economic development,

so we want to be right there with the new leaders to stress the importance

of what we're doing," said Peal. "But the SRNCL is a non-political

group - we don't know who will be in power, and we don't want to alienate

anyone by taking sides."

"We fear that too much pressure will be exerted

on the forest and other natural resources to provide economic development,

so we want to be right there with the new leaders to stress the importance

of what we're doing," said Peal. "But the SRNCL is a non-political

group - we don't know who will be in power, and we don't want to alienate

anyone by taking sides."

Evelyn Hightower, the treasurer of SRNCL, was traveling

through Liberia as an 'ecotourist' when she met Peal and became interested

in SRNCL. "I traveled to the neighboring countries and saw with my

own eyes how the desert is encroaching into the forest because of deforestation...

and then I understood why it's so necessary to preserve the small area of

rainforest that is left," Hightower said.

Evelyn Hightower, the treasurer of SRNCL, was traveling

through Liberia as an 'ecotourist' when she met Peal and became interested

in SRNCL. "I traveled to the neighboring countries and saw with my

own eyes how the desert is encroaching into the forest because of deforestation...

and then I understood why it's so necessary to preserve the small area of

rainforest that is left," Hightower said.

The SRNCL's current objectives include: educating the

general public in the United States and abroad about the need for conservation,

protecting endangered and rare wildlife species and ecosystems in Liberia,

organizing staff training programs for the Liberian Wildlife and National

Parks Division, restoring or replacing damaged or lost equipment and materials

at Sapo National Park, raising funds from charitable donations, and securing

grants from individuals, foundations and corporations. SRNCL holds public

meetings, conducts film shows and discusses conservation issues on the local

radio and press. SCNL also promotes nature clubs at schools and publishes

a newsletter for its members.

The SRNCL's current objectives include: educating the

general public in the United States and abroad about the need for conservation,

protecting endangered and rare wildlife species and ecosystems in Liberia,

organizing staff training programs for the Liberian Wildlife and National

Parks Division, restoring or replacing damaged or lost equipment and materials

at Sapo National Park, raising funds from charitable donations, and securing

grants from individuals, foundations and corporations. SRNCL holds public

meetings, conducts film shows and discusses conservation issues on the local

radio and press. SCNL also promotes nature clubs at schools and publishes

a newsletter for its members.

SRNCL's foresight is unique. The concept is to protect

a fragile environment before emerging economic and political forces damage

natural resources, instead of trying to fix after-the-fact environmental

problems like pollution and deforestation. And despite continuing civil

strife, most Liberians agree on the need to protect and conserve their common

ground.

SRNCL's foresight is unique. The concept is to protect

a fragile environment before emerging economic and political forces damage

natural resources, instead of trying to fix after-the-fact environmental

problems like pollution and deforestation. And despite continuing civil

strife, most Liberians agree on the need to protect and conserve their common

ground.

Karla Stang is an editor for the Times-Advocate in Escondido, an environmental

reporter, and a freelance writer. Raised in Hemet, CA, she moved to San

Diego 6 year ago and now lives in Golden Hill.