Where do the elephant seals go?

Seals and sea lions are such a fixture of life along the coast that

it's surprising how little we know about their movements. Researchers at

Hubbs-Sea World are starting to fill in the picture, with some amazing findings.

by Katy Koster

f you've spent much time on California beaches, chances

are you've seen seals and sea lions, playing in the surf or basking on the

rocks. The truth is, these ubiquitous mammals spend substantial periods

at sea each year, but their whereabouts and behaviors are relatively unknown.

f you've spent much time on California beaches, chances

are you've seen seals and sea lions, playing in the surf or basking on the

rocks. The truth is, these ubiquitous mammals spend substantial periods

at sea each year, but their whereabouts and behaviors are relatively unknown.

Scientists at the Hubbs-Sea World Research Institute are trying to change

that. Using the latest in satellite technology, they have been studying

the diving behaviors and foraging migrations of northern elephant seal bulls

for the past several years.

California sea lions and northern elephant seal populations

have increased substantially along the California coast during the past

several decades. The sea lion's increase has been quite apparent to sport

and commercial fishermen, and more recently each winter, to those living

along the coast of Washington, where the marine mammals have invaded the

waterways of Puget Sound to feast on migrating salmon. Near Pier 39 in San

Francisco and in Monterey Bay, large numbers of male sea lions have hauled

out and caused damage on private boat docks and fuel barges.

California sea lions and northern elephant seal populations

have increased substantially along the California coast during the past

several decades. The sea lion's increase has been quite apparent to sport

and commercial fishermen, and more recently each winter, to those living

along the coast of Washington, where the marine mammals have invaded the

waterways of Puget Sound to feast on migrating salmon. Near Pier 39 in San

Francisco and in Monterey Bay, large numbers of male sea lions have hauled

out and caused damage on private boat docks and fuel barges.

Return of the elephants

The rapid repopulation of California's waters by northern

elephant seals has been much less conspicuous, however, attracting only

minor public attention. Commercial hunters exterminated northern elephant

seals from California waters in the l9th Century - not until the 1950s did

elephant seals return to the Southern California Channel Islands to breed.

The rapid repopulation of California's waters by northern

elephant seals has been much less conspicuous, however, attracting only

minor public attention. Commercial hunters exterminated northern elephant

seals from California waters in the l9th Century - not until the 1950s did

elephant seals return to the Southern California Channel Islands to breed.

Today, San Miguel Island, lying about 70 miles west

of Los Angeles, hosts the world's largest northern ele-phant seal colony.

Seals congregate there in winter to breed and again in the spring and summer

to molt, but they are rarely seen during the ten months or so when they

are at sea. Indeed, their whereabouts for most of their lives are unknown.

Today, San Miguel Island, lying about 70 miles west

of Los Angeles, hosts the world's largest northern ele-phant seal colony.

Seals congregate there in winter to breed and again in the spring and summer

to molt, but they are rarely seen during the ten months or so when they

are at sea. Indeed, their whereabouts for most of their lives are unknown.

In 1987, Hubbs scientists began studying the diving

behaviors and foraging ecologies of elephant seals at San Miguel Island.

They document the depths and duration of the seals dives, the amount of

time seals spend resting at the surface between dives, and the sequential

patterns of dives.

In 1987, Hubbs scientists began studying the diving

behaviors and foraging ecologies of elephant seals at San Miguel Island.

They document the depths and duration of the seals dives, the amount of

time seals spend resting at the surface between dives, and the sequential

patterns of dives.

Hi-tech tracking

To track the seals, the scientists employ small electronic

instruments called time-depth recorders (TDRs). The original TDRs were large

devices, about 6 by 8 inches in size and weighing over 2 pounds. The newest

units are much improved, consisting of a 6-inch long cylinder about 1 1/2

inch in diameter. The TDR's are glued to the hair of seals just before they

leave the rookeries in late February. The housings for the TDRs must be

pressure-tolerant to protect the unit at depths to which seals were diving

- 1,500 to 2,500 feet, with the deepest recorded dive to about 5,000 feet.

To track the seals, the scientists employ small electronic

instruments called time-depth recorders (TDRs). The original TDRs were large

devices, about 6 by 8 inches in size and weighing over 2 pounds. The newest

units are much improved, consisting of a 6-inch long cylinder about 1 1/2

inch in diameter. The TDR's are glued to the hair of seals just before they

leave the rookeries in late February. The housings for the TDRs must be

pressure-tolerant to protect the unit at depths to which seals were diving

- 1,500 to 2,500 feet, with the deepest recorded dive to about 5,000 feet.

The TDRs provide information in two ways. First, the

unit records and stores data internally. The unit is retrieved when the

seals return to San Miguel Island in July to molt, and the data is dumped

for analysis. Second, the unit is able to send a small amount of data to

a satellite in polar orbit when the animal surfaces to breathe. The satellite

then retransmits the data to a ground station in France, and on to a computer

terminal at the Institute's headquarters on Mission Bay. Scientists can

determine the whereabouts of an animal in the middle of the Pacific Ocean

within minutes of that transmission.

The TDRs provide information in two ways. First, the

unit records and stores data internally. The unit is retrieved when the

seals return to San Miguel Island in July to molt, and the data is dumped

for analysis. Second, the unit is able to send a small amount of data to

a satellite in polar orbit when the animal surfaces to breathe. The satellite

then retransmits the data to a ground station in France, and on to a computer

terminal at the Institute's headquarters on Mission Bay. Scientists can

determine the whereabouts of an animal in the middle of the Pacific Ocean

within minutes of that transmission.

Adult male elephant seals dive continuously while at

sea for periods of 120 to 150 days in spring and early summer; it is a rare

event for a seal to spend more than five minutes at the surface between

dives that average 25 minutes. Because of limitations of previous satellite

systems, this pattern of infrequent and brief surface activity has made

it difficult to provide detailed movement information. However, recent improvements

in satellite technology now allow scientists to get locations of pelagic

(open sea) animals as well as dive duration and dive-depth measurements.

Adult male elephant seals dive continuously while at

sea for periods of 120 to 150 days in spring and early summer; it is a rare

event for a seal to spend more than five minutes at the surface between

dives that average 25 minutes. Because of limitations of previous satellite

systems, this pattern of infrequent and brief surface activity has made

it difficult to provide detailed movement information. However, recent improvements

in satellite technology now allow scientists to get locations of pelagic

(open sea) animals as well as dive duration and dive-depth measurements.

On the road

On the road

Analysis of the data gathered details some astounding

movements. Although routes differ slightly, northern elephant seals travel

north to the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands in approximately 40

days. They forage there for another 40 - 50 days, then take 40 - 50 days

to return to San Miguel Island. Elephant seals can cover more than 5,000

miles during annual migrations.

Analysis of the data gathered details some astounding

movements. Although routes differ slightly, northern elephant seals travel

north to the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands in approximately 40

days. They forage there for another 40 - 50 days, then take 40 - 50 days

to return to San Miguel Island. Elephant seals can cover more than 5,000

miles during annual migrations.

Diving patterns reveal uninterrupted diving for four

to five months. The records suggest that the seals forage continuously (diving

to depths of about 1,500 feet) during north- and southbound transits. Their

infrequent and brief surface appearances, as well as their offshore distributions

when at sea, explain why so few elephant seals have ever been seen away

from land-based breeding and molting sites despite their rapidly growing

numbers.

Diving patterns reveal uninterrupted diving for four

to five months. The records suggest that the seals forage continuously (diving

to depths of about 1,500 feet) during north- and southbound transits. Their

infrequent and brief surface appearances, as well as their offshore distributions

when at sea, explain why so few elephant seals have ever been seen away

from land-based breeding and molting sites despite their rapidly growing

numbers.

Institute studies were the first to document the pelagic

distribution and movements of northern elephant seals and demonstrated the

utility of this technology for studying the migrations and foraging ecologies

of marine mammals in general.

Institute studies were the first to document the pelagic

distribution and movements of northern elephant seals and demonstrated the

utility of this technology for studying the migrations and foraging ecologies

of marine mammals in general.

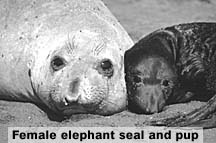

Studies are also conducted to examine annual variability

in foraging migrations and the extent of overlap in distributions of males

and females while at sea. Adult males and females separate - for reasons

as yet unknown - during two annual migrations covering 10,000 - 12,000 miles

each year.

Studies are also conducted to examine annual variability

in foraging migrations and the extent of overlap in distributions of males

and females while at sea. Adult males and females separate - for reasons

as yet unknown - during two annual migrations covering 10,000 - 12,000 miles

each year.

Information gained from Institute research provides

baseline data for sound ecology and conservation programs, and may provide

the foundation for legislation and environmental management decisions that

protect oceanic resources for generations to come.

Information gained from Institute research provides

baseline data for sound ecology and conservation programs, and may provide

the foundation for legislation and environmental management decisions that

protect oceanic resources for generations to come.

Katy Koster, a San Diego resident since 1985, lives in Normal Heights

and works in Public Relations at Hubbs-Sea World Research Institute, a non-profit

marine research foundation. The information in this report is based primarily

on the work of Dr. Brent Stewart.